A couple walks up a dirt road through the village of Roşia-Jiu, outside the town of Rovinari, where China hopes to finance a new coal power plant. Photo by Michael Bird.

Chinese Coal Power in Romania’s Rustbelt

Polluting coal facilities in southwestern Romania have adversely affected the well-being of the local population and the environment. But rather than phase them out, the EU member state is planning to build a new coal-fired plant, drawing on Chinese investment – even as the EU moves toward a zero-coal future.

As we near the town of Rovinari, a dense spiral of white smoke rises above the thick forested hills. These fog-like emissions billow from the chimneys of the 990 MW thermal power station that towers over the southwestern Romanian town, home to 11,500 residents.

Gheorghe Becheru, a 62-year-old retired engineer, and Gheorghe Gorun, a 70-year-old university professor, take us down a country lane in the village of Roşia-Jiu on the edge of town. There, in a weed-choked pasture, beyond rundown cottages with rusted roofs and broken wooden fences, a coal deposit has been opened like a dark gash – 20 meters high and 200 meters long.

Key Points

* As the EU plans to phase out coal-power by 2030, and to have net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 under the Paris Agreement, financing for coal power projects in the West has dried up. But in Romania the ready availability of Chinese investment is supporting plans for new coal power capacity.

* Romania has strong options for renewable energy like wind and solar power. However, the government has included lignite-based thermopower in its long term strategy, and commissioned the state-owned China Huadian Engineering Company (CHEC) for construction of a new 1 billion euro 600 MW thermal power plant in Rovinari.

* Beyond environmental pollution, the new power plant raises concerns about profitability. According to the EU’s emission trading scheme (ETS), the producer has to pay emission penalties. CHEC has reportedly negotiated for a long-term power purchase agreement or a guaranteed price for coal for the project, which would be illegal aid under EU legislation.

* CHEC invests its own money to cover only 300 million euro and is seeking a guarantee by the Romanian state for the remaining loan of around 700 million euro; as state aid for coal is illegal in the EU, the European Commission would need to sign off on such a deal.

* China’s interest for the Rovinari project is conceived by energy experts as part of a longer-term strategy to gain an important position in a European regional energy market: combined with Cernavodă Nuclear Power Plant, it would mean China controls 15 percent of electricity production in Romania.

“Welcome to hell!” Becheru says, his voice raw. A thick film of coal dust has gathered under his eyes. We cough sporadically as the caustic lignite dust catches in our throats.

Cattle graze next to the bank of coal. A transport belt, a rusty iron and steel contraption, winds over the fields, running right beside the houses, carrying the coal from the Roşia opencast mine at one end of the village to the Rovinari power plant three kilometres away. The contraption jangles and pounds at such a high volume it is almost impossible for us to hear each other speak.

The belt works at least eight hours per day, locals say, and sometimes runs without rest for 24 hours. As the coal is exposed to the air, the vibrations send up clouds of soot. It clogs our ears and mouths.

Two types of dust pollute the area: one that deposits quickly (particulate matter) and one that stays in the air for a long time (suspended particulate matter).

Meanwhile, the chimney stacks of the power station in Rovinari gush out a different cocktail of pollutants. According to Alexandru Mustata, campaign coordinator in Romania for Bankwatch, an environmental NGO, these include sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide and mercury. Rovinari is situated right in the middle of four opencast lignite quarries and a coal-fired power station. The town is criss-crossed by transport belts conveying fuel to the power station. Europe Beyond Coal, an environmental NGO, has ranked the plant among the most deadly coal power stations in the European Union.

Dozens of homes in Roşia-Jiu are affected by the noise and pollution from mining operations. Some residents, among those who are not working outside the country, are employed at the state-owned Oltenia Energy Complex (OEC), which operates the quarries and the power station. According to Becheru, heart and lung diseases are common here.

We meet local resident Constantin Lătăreţu, who was hospitalized for a full year for acute respiratory problems. His neighbor, retiree Valentin Purcaru, has chronic respiratory problems for which physicians have prescribed a breathing apparatus at night. With his family living on his illness pension and unable to work, Purcaru cannot afford the device. Purcaru’s neighbor, Emilia Cotoi, who tends livestock in the village, has a 35-year-old son with chronic asthma.

According to Purcaru, the mining company could do much more to help the community deal with the health and environmental problems caused by the quarry and power station, but so far it has done little.

“We are powerless,” he says.

The coal transport belt from the lignite mine cross the village of Roşia-Jiu. Photo by Michael Bird.

A New Era of Coal for Rovinari

Rovinari’s struggle with coal is visible in every aspect of life. On the day of our visit, the local car wash was very active, scrubbing down vehicles in a town where coal ash leaves a constant film.

Experts say that dealing with the town’s health and environmental challenges, and reaching broader climate objectives, requires reducing dependence on coal. But Rovinari is moving in the opposite direction. Even in the face of the European Union’s current ambition to phase out coal-power by 2030, and beyond that to its ambition under the Paris Agreement to have net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, Rovinari is anticipating a one billion Euro investment in a new coal-fired power plant.

Gheorghe Becheru, a retired engineer from the village of Roşia-Jiu, holds up a finger blacked with coal soot from the windowsill of a neighbor's home.

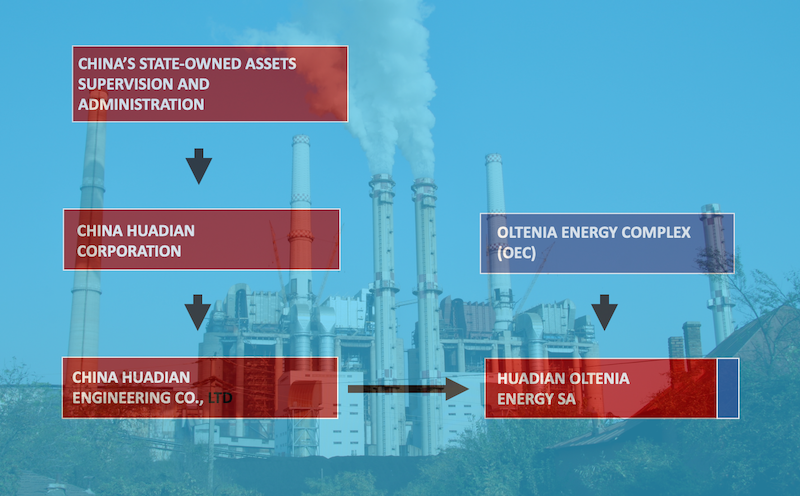

Enter China Huadian Engineering Company (CHEC), a wholly-owned subsidiary of the State‑owned Assets Supervision and Administration (SASAC), the government special commission in the People’s Republic of China that oversees centrally-owned companies.

In May 2012, the Romanian state launched a tender for the construction of a new 1 billion euro 600 MW thermal power plant in Rovinari, as part of its national energy strategy. The aim was to modernize and increase the efficiency of the coal-powered energy sector, where costs of production have been hit by the EU’s levy on CO2 emissions. CHEC beat out the Japanese Marubeni Corporation, the only other bidder, to invest in the project.

In the seven years since the tender, the project has suffered an array of problems. In 2014, Oltenia Energy Complex (OEC), the Romanian state-owned company behind the venture, revealed that plans had been put on hold, just days after an agreement for the joint venture to implement the project had been concluded at the Victoria Palace in Bucharest, the seat of government. Reports cited questions over the profitability of the proposed venture, and whether it would even be possible to recover the one billion Euro investment and production costs. The OEC responded that it would conduct a feasibility study.

Finally, in April 2017, in a sign that the project was again moving forward, the CHEC and OEC announced the establishment of a joint venture company, Huadian Oltenia Energy SA, in which Huadian is the majority shareholder with 91.06 percent. In August that year, the Romanian Ministry of Energy announced that it had officially resumed talks with CHEC for construction of the new power plant.

A look at the shareholding structure of China Huadian Engineering Co., Ltd, the partner in Romania, reveals that it is fully held by the Chinese government commission SASAC. Source: National Enterprise Credit Information System. Background image of Rosinari power plant by Michael Bird.

Generating Debate

The proposed coal-fired plant at Rovinari is one among a number of Chinese-invested projects in planning in the Balkans that has raised questions in the European Union and among environmental activists about the apparent disconnect between China’s global commitments on climate change and its underwriting of new coal-based facilities.

Globally, coal-fired electricity generation is a major polluter, accounting for 30 percent of global CO2 emissions in 2018. Under the Paris Agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the EU is trying to phase out coal-powered plants by 2030. However, not all EU countries have signed on – including Romania.

“Experts say that dealing with the town’s health and environmental challenges, and reaching broader climate objectives, requires reducing dependence on coal. But Rovinari is moving in the opposite direction.”

Plans to build new lignite power plants are underway not just in Romania and Greece, both EU member states, but also in several EU enlargement countries in the Balkans, including Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. It is a consensus among environmental policy experts that coal-based power generation is incompatible with Paris Agreement benchmarks, and there is little question that current plans for coal-based projects in the Balkans go against the agreement’s spirit.

Tellingly, international financial institutions have already phased out direct financing of coal projects in light of climate commitments. But the state-owned Export–Import Bank of China or other Chinese public banks have stepped in to fill the void, offering loans without which such projects would be impossible.

Analysts say that given current plans it is conceivable that up to 3.5 GW of coal plant capacity could go online in southeast Europe with Chinese financial support in the coming years. Consider that the massive Rovinari project, which could supply up to five percent of Romania’s energy needs, will have a lifespan of up to 40 years, and will not begin sending electricity to the grid until at the earliest 2023. That commits Romania to the operation of the plant up to 2063.

On March 12 this year, in a strategic outlook paper on China that characterized the country as a “systemic rival,” the European Commission noted the gap between China's commitments under the Paris Agreement concerning the curbing of domestic emissions – China being the world's largest emitter of greenhouse gas – and its support for new coal capacity around the world.

Cattle graze next to a seam of coal at the lignite mine in the village of Roşia-Jiu, Romania. Photo by Michael Bird.

“The EU welcomes the role of China as one of the main brokers of the Paris Agreement,” said the paper. “At the same time, China is constructing coal-fired power stations in many countries; this undermines the global goals of the Paris Agreement.”

Rationalizing Coal

Contrary to the broader European trajectory, Romania’s Energy Ministry has committed to lignite-based thermopower in its long term strategy until 2030. The Ministry’s secretary of state Andrei Maioreanu told a conference in Oslo in September 2019 that the building of a new 600 MW facility based on lignite, referring to the Rovinari project, was “compulsory” for Romania. The primary vision of Romania’s strategy, said Maioreanu, was to “grow the energy sector.” “This means to build, in a sustainable way, new production capacities and to improve existing production, transport and distribution of energy,” he said.

Currently, around 25 percent of Romania’s energy production derives from coal. The remainder comes from gas, hydroelectric, nuclear, wind and solar. According to Alexandru Mustata, Romania has strong options for alternative energy production, including wind power potential in the north of the country, and huge solar potential in the south. “Out of EU member states,” he says, “only Greece and Spain have better solar potential.”

But the Romanian government has continually insisted that coal-based facilities are essential, and that the country’s energy system is dependent on the plants of the Oltenia Energy Complex. Also in September, the government presented a study on the national energy grid that purported to show that energy losses from the shutdown of coal-fired power stations could not be recuperated by means of domestic production and energy imports. Separately, the government has emphasized that tens of thousands of workers and their families rely on the lignite quarries and power coal-fired power facilities of the Oltenia Energy Complex.

The Romanian government has continually insisted that coal-based facilities are essential, and that the country’s energy system is dependent on the plants of the Oltenia Energy Complex.

At present, Oltenia runs four thermal power plants in southern Romania, as well as the lignite quarries that provide a steady source of fuel. These support a total workforce of just over 13,000. The entire complex provides nearly a third of Romania’s electricity. But the facilities are aging and inefficient. The quarries date back to 1957, and the oldest power station was built in 1964. OEC argues that the replacement of old technologies will reduce dust emissions as well as pollutants like nitrogen oxide and sulphur dioxide.

According to Romanian energy expert Otilia Nutu, there are certainly marginal benefits to technology replacement. “You can say this unit is better than what OEC has in place,” she says. “So it is crowding out the worst capacities of OEC.”

But Romania is well-positioned to turn away from coal and toward more sustainable sources of energy, according to Alexander Mustata of Bankwatch. “Regarding the energy mix, it is much easier for Romania [to phase out coal] than for anyone else in the region,” he says. He notes that Poland has 78 per cent reliance on coal, while the Czech Republic has 50 per cent reliance on coal. By contrast, coal accounts for 30 percent of Romania’s energy total, while hydroelectric, gas and nuclear account for 30 per cent, 15 percent and 15 per cent respectively, while wind and solar account for 10 percent.

The cooling towers of the thermo power plant in Rovinari, Romania. Photo by Michael Bird.

“Romania has so many things in energy system that it would be so easy to replace coal for everything else,” he says.

OEC says that at this stage in planning for the project it is only “possible” that carbon capture and storage (CSS) technology will be integrated to reduce CO2 emissions.

Another argument proponents have made is that the coal-fired facility is essential to local job creation. According to a statement from OEC, the Chinese-invested project will mean securing more than 3,000 existing jobs. In addition, the construction phase of the project will create 4,000 jobs. Given China’s reputation for bringing in Chinese workers to handle the bulk of labour for its construction projects in Central and Eastern Europe, the company has reassured the public that most of these workers will be Romanian, coming principally from counties in the region.

The entry of a new investment player from China, the OEC says, will be a cash boon for Romania’s fading rustbelt, stimulating further investment in the area and enabling the export of electricity in the region. Answering environmental concerns, OEC has claimed that the facility will be an upgraded thermal power plant replacing older technologies currently in use, which date back to the 1970s. However state-of-the-art, it is clear that the new energy unit will be powered by lignite from nearby quarries owned by OEC, like the one rumbling through Gheorghe Becheru’s community.

China, meanwhile, has touted its credentials in promoting environmentally sound energy projects. After a meeting in June 2017 between Ambassador Xu Feigong and an energy consultant for the Romanian government, the Chinese Embassy in Romania posted a press release on energy cooperation over the Rovinari plant and other projects in which it said that, “Chinese enterprises have strict standards and rich experience in the efficient use of energy and in environmental protection.”

The Costs of Benefit

Beyond the larger concerns about the climate commitments of the EU and the Paris Agreement, there are a host of questions about the environmental impact, profitability and sustainability of the Chinese-invested project for the region.

First, environmentalists point out that increased power production will necessarily entail the expansion of lignite mines in the area, and an increase in polluting emissions – with a direct impact on biodiversity and adversely affecting the health of thousands of residents living close to the quarries and the power station.

![GoogleMaps - Shows four Quarries for lignite -[Tismana, Rovinari, Pinoasa, Rosia]. around town of Rovinari, where a thermo power plant from the 1970s stands.png](/sites/default/files/styles/fullwidth/public/2019-11/GoogleMaps%20-%20Shows%20four%20Quarries%20for%20lignite%20-%5BTismana%2C%20Rovinari%2C%20Pinoasa%2C%20Rosia%5D.%20around%20town%20of%20Rovinari%2C%20where%20a%20thermo%20power%20plant%20from%20the%201970s%20stands.png?itok=OiW8qX_K)

A satellite image of Rovinari shows the locations of four lignite mines on the outskirts of the town. Image by Ionuţ Dulămiţă and Michael Bird.