German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Photo by EU2017EE Estonian Presidency, available at Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.

What Makes Angela Merkel Cry?

When it comes to Europe’s relationship with China, perceptions in the Chinese social media space could be too important to ignore.

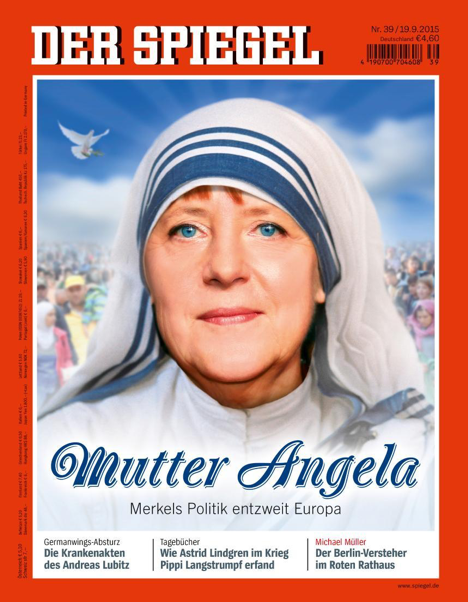

The language used on Chinese social media to describe events in Europe, and China’s relationship with the continent, is nothing if not colorful. Germany’s chancellor is sarcastically referred to as “Holy Mother Merkel,” the most prominent face of the “white left.” There is talk of “face slapping,” the “Thucydides trap,” and “mosques springing up like mushrooms.”

But beyond the colorful rhetoric — what does it all mean? What dominant themes and frames construct China’s image of Europe? And what implications do these have for Europe’s relationship with China? Based on a dataset of more than 11,000 social media posts for Europe obtained from WeChat public accounts over the full year 2018, Echowall sought to answer these questions.

QUICK TAKE

Here are some basic findings of our social media study of Chinese perceptions of Europe:

- In light of tensions between global powers, Europe is often portrayed as having a secondary, sideline role, either suffering indignity in the shadow of U.S. hegemony, or standing up against the United States — alongside China. This overarching narrative is deployed to legitimate China’s position against the U.S, or as a counter-balance to its interests.

- Where Europe-specific issues are concerned, there is a deep polarization of perception on the Chinese side. On the one hand, Europe is perceived as being in the midst of a prolonged disaster owing to the refugee crisis and its imagined fallout. Simultaneously, however, it is portrayed as an ideal destination for immigration.

- A substantial proportion of social media content referring to Europe in the Chinese social media space can be classified as “junk news,” often adopted or adapted from unreliable sources outside China.

Both European and Chinese decision-makers should take these gaps in perception seriously, as a distorted perception does not serve to build a rational relationship.

THE POWER OF JUNK

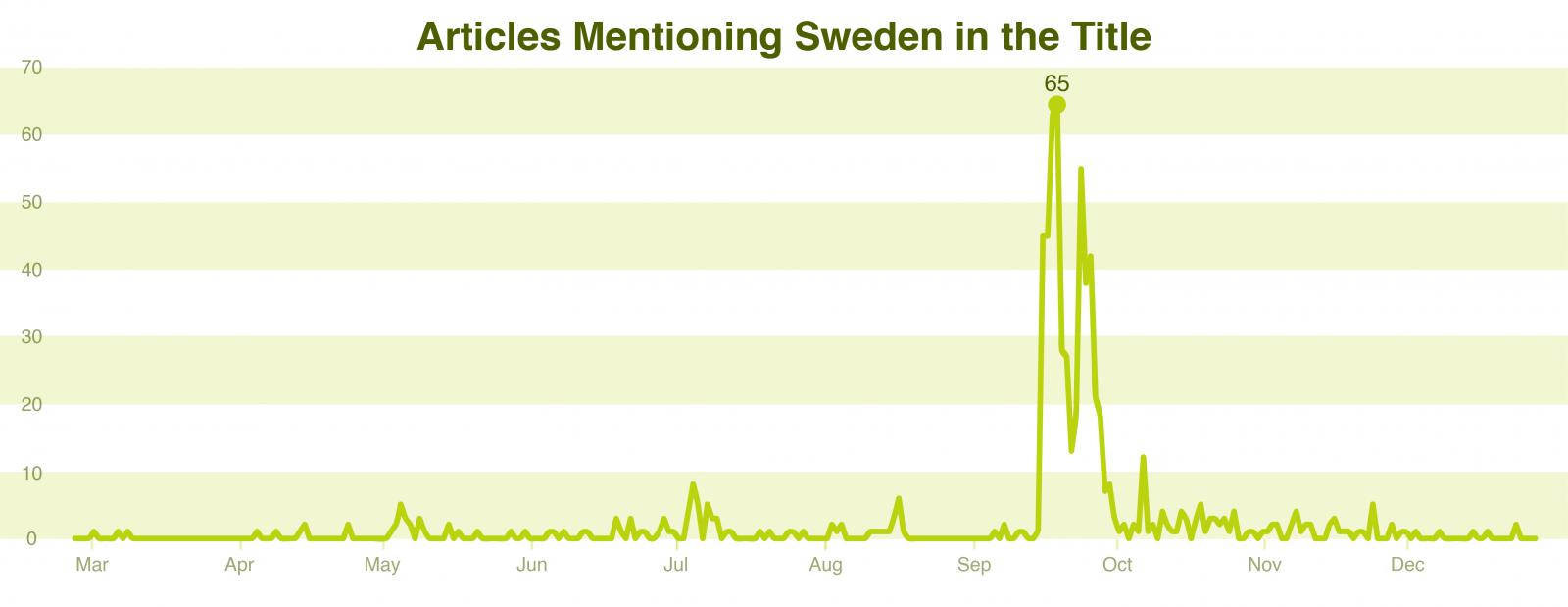

There is increasing awareness among Western politicians and academics that social media have become the center stage of information consumption and are shaping public opinion on political issues. Research has shown convincingly, for example, that junk news dominated Twitter and Facebook in the lead-up to the US midterm elections in 2018. International far-right networks and Kremlin-sponsored media have also been linked to a concerted smear campaign targeting Sweden’s reputation around the 2018 Swedish elections.

Both European and Chinese decision-makers should take these gaps in perception seriously, as a distorted perception does not serve to build a rational relationship.

While there are a growing number of studies exploring the use of platforms such as Twitter and Facebook to engage in “smearing” campaigns and other forms of interference, less attention has been paid to the framing of international issues and national politics in the Chinese social media space. What kind of information do people receive concerning Europe and Sino-Europe relations?

This is Echowall’s first exploration into the picture of Europe in Chinese social media using data derived from WeChat public accounts.

Both European and Chinese decision-makers should take these gaps in perception seriously, as a distorted perception does not serve to build a rational relationship.

Since 2015, WeChat has been China’s most important social media platform for chatting, information sharing and much else. Photo by Lin Sinchen available at Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.

WHY WECHAT?

WeChat is the dominant social media service in China with more than one billion active users in 2018 (according to data from its parent company, Tencent). As a “super app” that integrates a broad range of functions — everything from private and group messaging to online shopping, gaming, e-learning, food delivery and bill payment — WeChat has become an indispensable part of everyday life for Chinese internet users.

Aside from individual user accounts, WeChat provides a “public account” service (公众号) for traditional media, corporations, government institutions, and private persons operating so-called self-media, or zimeiti (自媒体). While individual accounts are used for communication within one’s personal network of friends, family and acquaintances, public accounts provide content to a broader audience.

Normally, WeChat permits each public account to post just one to three articles per day. In 2018, there were around 500,000 public accounts actively competing for readers attention in China, with roughly five billion daily page views. Over 80 percent of Chinese internet users are consuming news and information through social media. Therefore, WeChat public accounts provide a virtual arena crucial for public discussion and the formation of public opinion in today’s China.

Working in partnership with the Journalism & Media Studies Centre at the University of Hong Kong and its WeChatscope Project, Echowall isolated a database of posts on WeChat public accounts dealing with Europe. Through a technical web “scraping” system, the WeChatscope Project studies censorship on WeChat’s publicly accessible pages. In 2018, the project tracked more than 4,000 accounts to yield a database of more than one million articles. This formed the basis of our study.

WHAT IS EUROPE?

To study Chinese perceptions of Europe, one first has to define Europe — a question that can prove difficult even for Europeans.

Echowall and WeChatscope began by conducting a keyword search to collect relevant data by using the Chinese characters for “Europe” (欧洲) and the “EU” (欧盟), as well as names of each member state of the Council of Europe plus Belarus and the Vatican. We then excluded from our “Perception of Europe” dataset any data focusing chiefly on Russia and Turkey. (We plan in the future to devote separate studies to Chinas relationship with each of these countries).

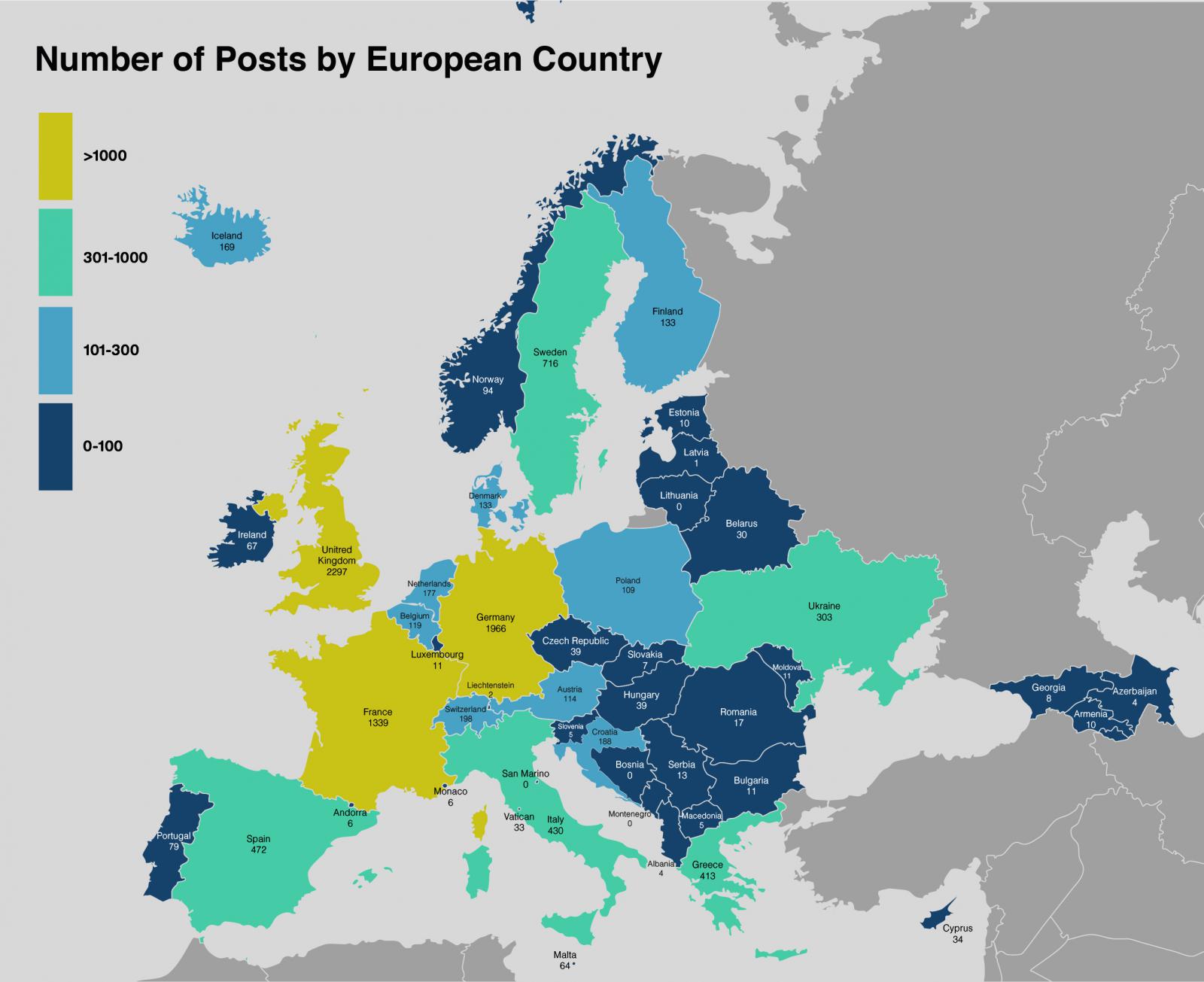

In order to attract clicks from as many potential readers as possible, public accounts on WeChat have developed the strategy of using lengthy headlines to include as much information as possible. With this in mind, we conducted a keyword search within the headlines of our body of one million WeChat public account posts to isolate a data set of more than 11,000 posts dealing with Europe or various European countries. Of the total posts, roughly 2,000 refer either to “Europe” or the “EU.”

Given the huge diversity of content on the internet, it is not possible to capture all relevant data. The purpose of our study was first to highlight important trends and identify important frames applied in Chinese cyberspace for perceiving Europe, then to look more closely at relevant case studies.

But the first question we sought to answer was: Which user accounts are creating and sharing information about Europe on WeChat?

WHO'S TALKING ABOUT EUROPE?

A key finding that may or may not surprise readers is that one of the most important groups of accounts consists of commercial entities, often registered outside China and by overseas Chinese, whose primary motivation is to promote immigration and real estate investment in Europe, as well as the sale of European products.

One of the most productive accounts within our dataset, for example, was European Homebuyer Web (欧洲购房网) , which accounted for a total of 397 WeChat articles referring to various European countries. The account is operated by a company headquartered in Seattle that provides real estate consulting services to Chinese investors. Their posts do not necessarily make explicit reference to their own business, but they always describe Europe as an ideal destination for prospective real estate buyers, with a “dreamlike” environment, plentiful cultural resources and good education systems for families with children.

Another main group consists of public accounts operated by traditional Chinese media outlets such as the Chinese-language edition of the Global Times (环球时报), a tabloid spin-off of the Chinese Communist Party’s official People’s Daily newspaper, and Reference News (参考消息), a mass-circulation daily digest of selected foreign news that is published by China’s official news agency, Xinhua. The accounts of these two media ranked second and third respectively in terms of the total number of posts in our dataset, each with more than 200.

Both the Global Times and Reference News are Chinese dailies focusing on international news. Founded in 1931, Reference News was for many decades in China the only media institution officially permitted to translate and publish news articles from foreign media. While published by the People’s Daily and often clearly reflecting the policies and agenda of the leadership, the Global Times is also commercially driven, with a wide readership. Some Chinese media experts have praised the newspaper’s ability to “combine the function of guiding public opinion with readability,” while others have criticized it as an egregious example of “commercial-nationalism”, lacking professionalism and credibility.

The third group of accounts in our dataset are so-called “self-media” entities — or WeChat-based publications not operated by traditional media — dealing specifically with military-related topics from a clearly nationalistic point of view. In contrast to Europe, military themes are quite popular in China, and some of these self-media accounts can gain massive audiences as news accounts, even something attracting venture capital. One such example is Tiexue.net (铁血军事), whose name translates literally as “Blood and Iron Military Affairs.” The account, which has two million subscribers, is now listed on China’s over-the-counter exchange. Another account in this group is Jinri Pingshuo (今日平说), which is operated by influential internet writer Zhou Xiaoping (周小平), whose penchant for populist, anti-American comments brought him to the attention of propaganda officials in 2014, when Zhou was singled out for praise at the Party’s “Forum for Literature and Art.” During that forum, using a CCP phrase for patriotic and non-critical language, Xi Jinping encouraged Zhou to continue “carrying forward positive energy” online.

WHAT ARE THEY SAYING?

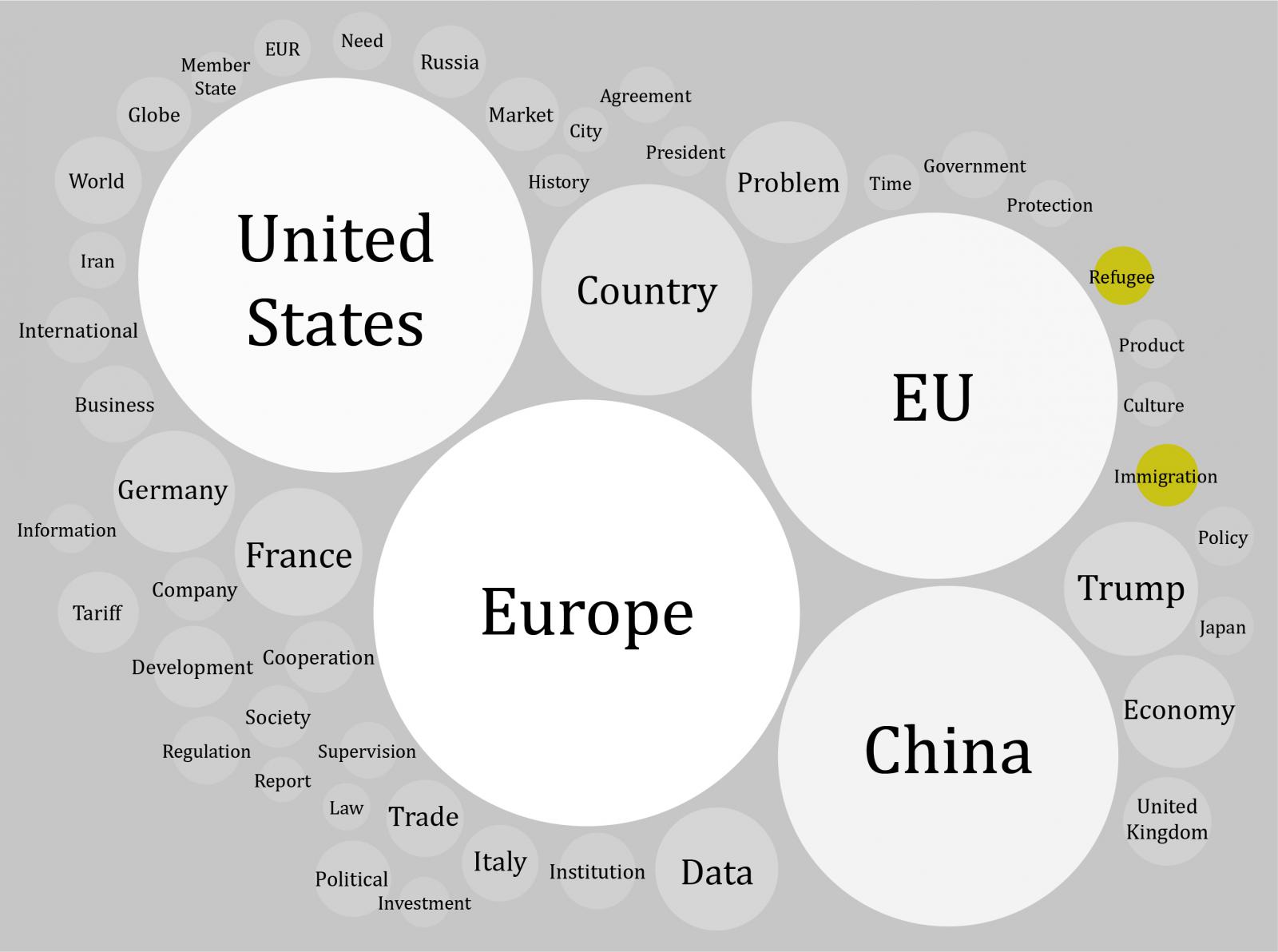

When social media accounts in the dataset discussed “Europe” or the “EU,” the most widely used keyword was in fact the “U.S.” (美国) — quite a telling detail about how Europe’s role is perceived. Likewise, in our Europe-related posts, the leader with the highest profile is not German Chancellor Angela Merkel or French President Emmanuel Macron, but rather U.S. President Donald Trump. “Trump” (特朗普) appears in the dataset with at least ten times the frequency of either Merkel or Macron.

And what of Xi Jinping? It is interesting to note that Xi is scarcely mentioned at all in social media posts about Europe, in quite striking contrast to his dominance in related reports in traditional Chinese media.

Aside from terms referring to general economic topics, discussions around Europe in the Chinese social media space frequently touch on “refugees” (难民) and “immigration” (移民) as issues specific to Europe.

Before going more in depth into two interesting case studies specific to European countries and leaders, let’s look a bit more indepth into three prevailing themes regarding Europe in the Chinese social media space: 1) Europe and the U.S., 2) the European refugee crisis and 3) Europe as a top migration choice.

Theme: Europe Should Unite with China in Defending Globalization

In the dataset, nearly 400 posts deal in the headline with both Europe (or the “EU”) and either the U.S. or Trump, indicating an interest in constructing or defining Europe in terms of international power relations. These posts suggest a strong tendency toward dramatization of events as conflict, with terms like “drawing the sword” (拔剑), “opening fire!” (开打!), “face slapping” (”(打脸), “a tooth for a tooth”(以牙还牙) and “turncoat” (倒戈). Terms like these lend an air of drama to world affairs.

In this drama, Europe is generally cast as the “little brother”(小弟) subjected to bullying by the hegemonic United States, but “too foolish and naïve” to resist or fight back. Or, alternatively, Europe is seen as the betrayer who finally stands up against the hegemonic power — alongside China.

The accounts most actively contributing to this narrative are Reference News and the Global Times, along with Zhou Xiaoping’s Jinri Pingshuo. Neglecting to provide any sourcing whatsoever for his arguments, Zhou gives free rein to his imagination as he interprets global events: “When the EU set up the eurozone with the aim of becoming economically independent of the United States, the latter reacted with fury and unleashed war in Kosovo and in Ukraine through NATO, upsetting the growth of the Euro.” At another point, he writes: “Without military independence, Europe is like a flock of sheep without fences and unprotected from the attack of the wolf — the United States.” “The best strategy for Europe,” Zhou adds, “is to cooperate with the mysterious great nation in the East.”

In contrast to the fact-free and often fictional style of self-media on WeChat, the content of Reference News appears to be more credible, apart from its often-sensational headlines. But the account, like its parent newspaper, makes generous use of a method called “selective editing,” or zhaibian (摘编), in which elements from foreign media are picked out and reorganized in such a way that they support China’s official position on foreign affairs, often falling into established Chinese state narratives.

For example, in a July 2018 essay for Foreign Policy called “The World Order Is Starting to Crack”, Stewart Patrick, director of the International Institutions and Global Governance (IIGG) Program at the New York-based Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), criticized Trump’s trade protectionism for having “allowed mercantilist China — which flagrantly steals intellectual property, restricts foreign investment, and protects entire sectors from foreign competition — to portray itself as a bastion of multilateral trade.” Patrick argued that Trump’s actions had pushed the European Union into China’s arms. In the Chinese version of this article appearing at Reference News, emerging in the dataset, all remarks critical of China are removed, leaving the apparent suggestion from an American foreign relations expert that the European Union should cooperate with China in order to defend globalization.

Generally speaking, in China’s social media sphere, the interpretation of international power relations is firmly in the hands of official state media and self-media like Jinri Pingshou that have a nationalistic perspective. In the global affairs landscape they construct, Europe plays only a supporting role — bolstering Chinas position against the United States.

Theme: “Europe-stan is Burning!”

About 200 posts discussing Europe in the dataset make reference to the issue of refugees and immigration. It is perhaps not surprising, given the intensity of discussion of these issues within Europe, that these are framed by Chinese accounts as issues dividing Europe and precipitating the rise of far-right movements across the continent. But at least a third of these articles can be classified as heavily biased — relying on opaque or untrustworthy sources, showing manipulation of content, or prone to false generalizations, abusive language or conspiracy theories.

As a rule, the distortion of information begins with sensational headlines for the posts. Headlines like: “History Will Remember Merkel As the Destroyer of Europe!”; “Breaking: Refugee Riots Are Sweeping Across Sweden, Europe-stan is Burning!”; “Authoritative Report: Europe is Islamizing at a Speed of 230%, France Has Already Passed Critical Point!”

In these posts within the dataset, there are two principal targets of blame for the perceived “disaster” facing Europe, which generally follow the explanatory logic of conspiracy and naivete, as follows:

1. Conspiracy: The Arab Spring uprisings and the NATO-led military intervention in Libya in 2011 were instigated and orchestrated by the U.S. with the hidden objective of sowing chaos in Europe by uprooting millions of people in the Middle East from their homes. American motives are explained through the notion of Thucydides Trap (修昔底德陷阱) — Harvard University political scientist Graham Allison’s notion that war can be precipitated when an established power fears a rising power. Interestingly, this term is applied almost uniformly in the ongoing discourse — both in the U.S. and China –when the trade war is discussed. This narrative in the Chinese social media space has little to do with Europe, but rather serves to support the framing of the U.S. as an evil, hegemonic power that creates chaos everywhere.