Chinese shoppers in Beijing. Photo by klarititemplateshop.com available at Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.

Let's Talk About China's GDP

Through the strength of its economic growth figures year after year, China has projected an image of fundamental economic strength. But a closer look at the numbers exposes profound structural issues that should help cool down fear and envy in the West.

However you read China’s economic numbers, they point to dramatic change over the past four decades. Many of these numbers will already be familiar to European readers. But let's run through some of the essentials — before we subject the assumptions that come with them to greater scrutiny.

First, according to official data, the average GDP growth rate in China from 1978 to 2018 was 9.5 percent. Per capita GDP rose during that period from 100 dollars to more than 9,000 dollars. China’s total GDP last year exceeded 90 trillion yuan, or about 13.6 trillion dollars at current rates of exchange.

KEY POINTS

- Since the "opening up and reform" policy, economic performance has become a core source of ruling legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party. To deal with this political imperative, statistical distortions and manipulations are inevitable.

- With the pattern of infrastructure-led GDP growth, China's apparent economic strength does not reflect the efficiency of resource usage and wealth accumulation.The high-speed rail network with its expanding public debt, for example, is criticised as "a gray rhino".

- The largest danger for China's economy is its high dependency on the overheated real estate market, more than a quarter of outstanding loans in the financial system is related to this sector, and more than 77 percent of household assets are vested in housing.

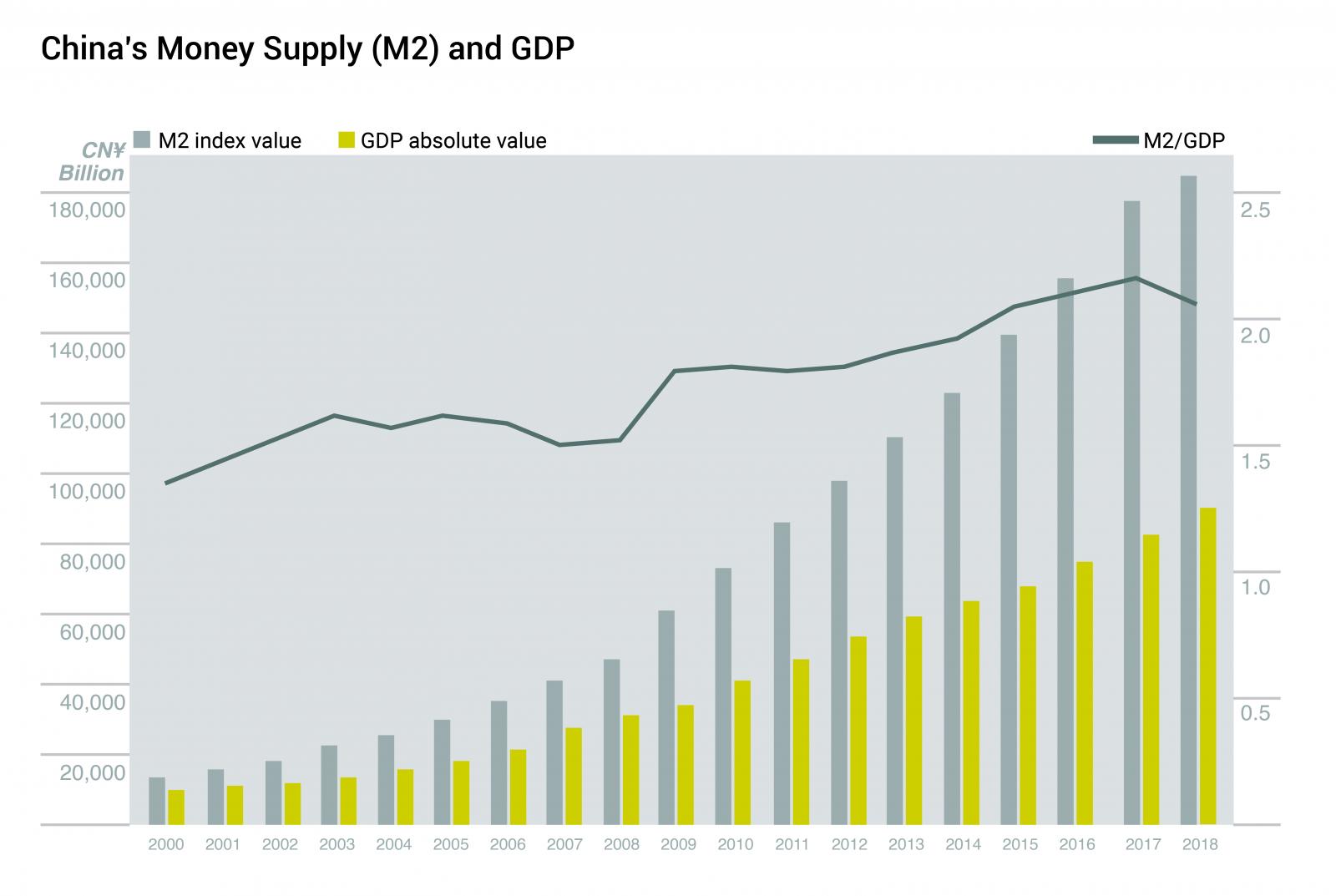

- To delay the bursting of the real estate bubble, China has been pumping liquidity into the economy so the gap between M2 and GDP is widening. The US accuses China for gaining an unfair advantage by lowering its exchange rate. But the real problem is, with abandoning capital controls and free convertibility of the yuan against the dollar, the RMB would go into free fall.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) puts total global GDP in 2018 at 84.84 trillion dollars, which has China accounting for 16.03 percent, second only to the United States (with a GDP of 20.5 trillion dollars). Globally speaking, this means that China is now the world’s second-largest economic power.

Changes to China’s economic landscape behind the figures have been equally profound. The middle class — as determined by home and car ownership — has now reached roughly 300 million. One in 900 Chinese are US-dollar multimillionaires, and one in 14,000 Chinese are billionaires. As a result, China has become the world’s largest market for luxury cars as well as other luxury goods.

Who gets to claim credit for what some have called a “miracle”?

This is a subject of some disagreement. But it is fair to say that China’s rapid economic growth over the last 40 years owes to a large extent to the policy of so-called “opening up and reform,” or gaige kaifang (改革开放), and the Chinese Communist Party leadership can certainly accept some kudos in this regard. The policy relaxed restrictions on economic activity; it spurred people on in their desire to make money; it improved the rules of the economic game; and in most cases, it encouraged respect on the part of the government for basic property rights and the validity of contracts.

But if we may break from all of this positive talk, it’s important to note that some troubling signs have emerged in recent years. Part of this has to do with the values promoted and defended by this now undisputed economic power. Despite dramatic changes to China’s economy and society, the Chinese Communist Party's tolerant attitude toward economic development is driven purely by opportunism. Economic opening can be abided only so long as it sustains the Party’s long-term monopoly on political power.

For investors and entrepreneurs in China, this is an underlying source of risk and concern—the sense that ideology could turn the tables at any moment.

At the same time, even as it celebrates its newfound international role, China is undergoing a process of state “rejuvenation” driven by a deep current of nationalism — the operative phrase for Xi Jinping being “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation." This has contributed to the sense globally that China presents a challenge to the international order led by the United States. Negotiations between China and the US over the past year have failed to resolve deep-rooted differences, and may actually have intensified the sense of conflict.

Negotiations between China and the US over the past year have failed to resolve deep-rooted differences, and may actually have intensified the sense of conflict.

For several years now, it seems many people in the West and elsewhere in the world have gotten hot under the collar about China and the challenge posed by its newfound economic and political strength. At this point, it is a good idea, therefore, to re-examine the real picture presented by the Chinese economy, and to recognize the deep structural problems it faces. Part of the problem stems from China’s political system itself, which is hardwired to inflate its virtues and downplay its vices in such a way that we can never accept its numbers at face value.

It’s possible that a more sober look at China’s economy might cool the fires just a bit and help avoid serious miscalculations from which none of use will benefit. For the sake of everyone who has a stake in the global economy — and that’s all of us — better calculations are in order.

China’s Paradoxes

As I said before, the Chinese Communist Party is within its rights in claiming some of the credit for China’s economic development over the past four decades. But the truth is that it often demands too much of the credit. After the Communist Party came to power in 1949, decades of poor governance — and that is really putting it mildly — resulted in tremendous tragedies that prompted profound questions about the legitimacy of the Party’s rule.

Deng Xiaoping arrives in the United States in 1979, just as economic reforms in China are getting underway. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.

The policy of “opening up and reform” initiated after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 was meant initially to avert economic collapse, and only later served as a source of ruling legitimacy as the economy developed successfully.

The deeper question of the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party has hung constantly over China’s economic development these past 40 years, which means that recession, so to speak, is off the table. Keeping the economy in positive territory is not just an urgent economic matter, but an even more urgent political one. Whatever the real economy looks like, the apparent economy must never be allowed to look like it’s in bad shape.

To deal with this political imperative, special consideration or tailor-made economic results are sometimes necessary within the statistical system in China. If economic performance deteriorates, statistical distortions and manipulations are inevitable. Aside from the overarching Party imperative of legitimacy and economic performance, we must consider that GDP growth has always — over the past 40 years, at any rate — been an important factor considered when the Communist Party evaluates the political performance of officials to consider promotion.

Statistical secrets are concealed within this malformed system, and in order to identify and understand these secrets, we must look at the Chinese economy differently — arriving at quite a different picture.

One challenge is to deal with frequent reporting of obvious paradoxes. For example, how can China report double-digit increases in industrial production when both electricity consumption and taxable sales experience significant declines. That simply isn’t possible. An increase in production should mean manufacturers are using more, not less, energy.

This is why The Economist originally introduced the so-called “Li Keqiang Index,” named for China’s premier, as an alternative way of assessing economic growth in China. The index was based on three key indicators: electricity consumption, rail freight and bank loans. The index was considered a better indicator to reflect China’s economic reality than official GDP figures, and for a little while, the index became popular even in official Chinese media outlets. That popularity was short-lived, however, because the index, and the potentially embarrassing gaps with the official numbers, ran up against the political imperative.

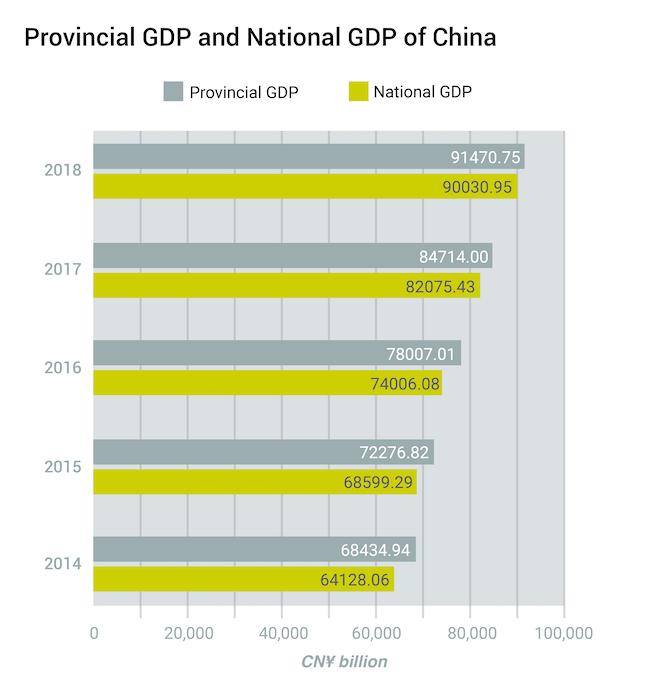

One of the most typical distortions of economic statistics in China can be spotted by looking at difference between the aggregate data of each province and total countrywide data. For nearly every year of the past decade, going back to 2009, China’s provinces have reported more aggregate GDP than is reported for the country by the National Bureau of Statistics. In 2017, for example, the national figure was nearly 1 trillion RMB short of the aggregate GDP of the provinces.

From time to time, domestic media criticize these statistical distortions. In December 2015, a report by the official Xinhua News Agency reported exaggeration of economic data in three northeastern provinces that was so extreme that some counties in this region were reported to have GDPs exceeding that of Hong Kong.

In 2018, both Inner Mongolia and the municipality of Tianjin were found to have laundered their GDP figures for 2016. Under immense public pressure, Inner Mongolia eventually reduced its aggregate industrial output value for 2016 by 290 billion yuan — wiping 40 percent off of its original figure. The Tianjin Binhai New Area, a district under the jurisdiction of Tianjin, cut its reported 2016 GDP by 33 percent.

The politics and mathematics behind these reductions are complicated, but the cases certainly show just how flexible and arbitrary official data can be.

Consistently over-reported provincial aggregate GDP figures in China, surpassing national GDP, can be seen as statistical proof of a political system in which officials are under pressure to exaggerate their merits.

Senior officials in the National Bureau of Statistics have previously gone on record saying that the sense of “rule of law” is poor in the reporting of economic numbers, and that statistical fraud is endemic in spite of the fact that there are laws on the books clearly prohibiting such practices. The laws, however, actually have tough competition when it comes to the rules of political advancement. Many provinces are driven to falsify date in the first place in order to compete for position and ranking, which is linked to career prospects.

Consistently over-reported provincial aggregate GDP figures in China, surpassing national GDP, can be seen as statistical proof of a political system in which officials are under pressure to exaggerate their merits.

Naturally, the gap between provincial and national figures has also led to more fundamental questions about whether official statistics are credible at all. In fact, the reputation of China’s national statistics hardly fares any better.

When numbers are too perfect, this naturally leads to suspicion. This principle often applies to China when published official data on GDP growth lines up perfectly with official GDP goals. Are Chinese economic prognosticators just that good? Or are they self-fulfilling their own prophecies?

In 2017, for example, the official GDP target was set at 6.9 percent. When the results came back for the first quarter of 2017, China had recorded a GDP growth rate of, you guessed it, 6.9 percent. In the second quarter, the GDP growth rate again came out to 6.9 percent. Growth rates for the third and fourth quarters followed the pattern. There were no surprises. But the perfect figures prompted doubts and suspicions about the accuracy of the official data.

Some international research institutions have suggested that China’s real GDP growth rate could be much lower than the published figures. The Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think tank, published a research report in March this year that systematically analyzed Chinese economic data from 2008 to 2016. The report concluded that the annual economic growth rate had likely been exaggerated by 2 percentage points in recent years, and that as a result China’s total economy might be about 12 percent smaller than official data would lead people to believe.

The Brookings report reinforces longstanding doubts about the veracity of official statistics on China’s economy, and it suggests the economy might be not just objectively smaller than currently believed, but performing more poorly.

Breaking and Building

Even if we do have accurate numbers for GDP as a reflection of output for a given period of time, GDP often fails to reflect how efficiently or inefficiently resources were utilized. In countries like China, official data can be deceptive on this count as well — and GDP in particular can be a poor indicator of real economic results and wealth accumulation.

China is known for its seeming obsession with the construction of property and infrastructure. Is this the most efficient use of resources? Photo by Gauthier Delacroix available at Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.

A friend of mine living in Shenzhen has made an observation that I think is perhaps very significant — and that is that the local government in the city, which is one of the country’s most vibrant economically, has the habit of allocating funds toward the end of each fiscal year on the building and repairing of roads. The phenomenon, he says, is unmistakable. Workers hired by the government dig up roads that are in perfectly serviceable condition and then repair the same roads all over again. In some cases, they uproot perfectly good trees on the roadside and then replant them right where they were.

As government budgets for such projects expand, the activity becomes an ever-present part of daily life. Roads heading east, north, west and south all seem to be in a state of repair, the state-of-the-art digging machines buzzing with activity all day long.

This activity — the unending destruction and re-construction of the city — should not be at all surprising if we understand the political imperative of GDP reporting. It is a key mechanism of inflating GDP while satisfying a handful of vested interests with the government contracts to do such work. Macro-level analysis of economic growth patterns in China would suggest that a large proportion of GDP is achieved through inefficient, ineffective and completely unnecessary economic activities. My friend just happened to observe this happening at street level through his daily observation.

The Chinese government has actively practiced Keynesianism for the past several decades, applying increased government expenditures to stimulate economic data growth — if not necessarily the economy itself — through depressive cycles. This can happen through proactive fiscal spending (the redundant repair of Shenzhen roads being one of many examples), or through large-scale investment in infrastructure that can be used to hedge against or postpone impacts of the economic cycle.

The question of whether these economic measures can actually lead to wealth accumulation or public happiness is another story altogether.

High-Speed Waste

Perhaps one of the best showcases of this pattern of infrastructure-led growth is the construction of China’s high-speed rail network. Since 2005, the building of the high-speed rail system has been one of the country’s most important infrastructure projects. Today, China’s high-speed rail system boasts the largest total mileage of any comparable network in the world, and high-speed rail is hailed as a source of immense national pride.

Towering behind this signature national network, however, is a mountain of public debt that cannot be acknowledged or talked about. The national railway operator alone has born total debt in excess of 5 trillion RMB, or 726 billion dollars. This is one state-run company incurring debt greater than the GDP of Switzerland or Taiwan (705 billion and 589 billion respectively in 2018).

A high-speed train waits in the Suzhou Railway Station. Image by Sharon Hahn Darlin posted to Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.

But with the exception of just a handful of high-speed lines, such as the Beijing-Shanghai and Beijing-Guangzhou lines, nearly all of China’s high-speed rail routes are operating under capacity, incurring losses on a daily basis. The Lanzhou-Xinjiang line, built with capacity to run more than 160 pairs of high-speed trains daily only runs just four pairs daily. The income derived from the line is not even sufficient to pay the line’s electricity bill.

China’s dense high-speed rail network may be the world’s largest, but it also has one of the lowest transport densities in the world. The network is a substantial financial risk for the country — and a dear price to pay for national prestige. According to official data, between 2013 and 2017, the China National Railway Corporation had to make RMB interest payments of 215.7 billion (US$31 billion), 330 billion (US$48 billion), 338.5 billion (US$49 billion) and 540.5 billion(US$78 billion) in order to service its mountain of debt. Since 2016, interest payments have exceeded the network’s total operating income.

Economically speaking, China’s high-speed rail network is a disaster of massive proportions. Earlier this year, Caixin, one of China's most influential financial media outlets, initiated a public debate about the debt problem of the high-speed rail network, calling it “a gray rhino”: a highly probable, high impact yet neglected threat.

To exacerbate matters, it is a disaster that is moving forward at high-speed, with debt constantly expanding.

Economically speaking, China’s high-speed rail network is a disaster of massive proportions.

And China’s high-speed rail network is just one of numerous examples of how China’s GDP has been distorted through wasteful spending. We can add to the long list many road and highway projects, subway networks, airports, and a slew of other government projects. All of these have contributed to China’s enviable GDP growth, but with extreme inefficiencies.

No discussion of China’s GDP can be complete, of course, without touching on the country’s real estate sector.

Jack's Beanstalk

Since 2000, China’s real estate market has grown at a prodigious rate. In 2000, Chinese residents bought 143 million square meters of commercial housing, and the average selling price nationwide was 2,103 RMB (US$305) per square meter. By 2018, the average transaction price of commercial housing had rocketed to 8,544 RMB per square meter (US$1,241). All told, real estate and related industries account for more than a quarter of total private fixed-asset investment in China, and real estate has become an undisputed pillar industry in the national economy.

But the real estate sector in China is a massive bubble, a trend we can see clearly if we look at the ratio of housing sales prices to media household incomes.

A 2016 report by a research group from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences revealed that the price-to-income ratio in Beijing was 33.2. In Shanghai, the price-to-income ratio was 31.9. And in Shenzhen, it was the highest of all, at 33.5. Even if this set of data is not completely accurate, there is no disputing that the price-to-income ratio for housing in China’s first and second-tier cities is higher than in most major cities in the world.

Housing prices have not surprisingly been a constant source of public resentment in China.

China’s top property developers, which have expanded dramatically over a short period of time, are all driven by massive debts. The top five developers in terms of sales have debts with interest totaling up to 1.585 trillion RMB. These include: Evergrande Group (debt of 676.2 billion ; Country Garden (debt of 294.5 billion); Vanke (debt of 179.4 billion); Sunac Real Estate Group (debt of 209.8 billion); and Poly Real Estate (debt of 225.1 billion). These debt figures are given by the Hong Kong stock Exchange, where all of these companies are listed.

China’s growing real estate bubble is doubly concerning when you consider that real estate has become the most important carrier of Chinese household assets. According to the “2018 Urban Household Wealth Report” jointly released by China Guangfa Bank and Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, as much as 77.7 percent of household assets in China are vested in housing. In Beijing and Shanghai, this figure could be as high as 85 percent. By comparison, the average figure in the United States is just 34.6 percent.

Visitors to Beijing's Urban Planning Exhibition Center look at a scaled models of the the Chinese capital's urban development. Photo by "cea+" available at Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.

It’s clear that the property sector, by far the most important sector in China’s economy, is solidly in bubble territory, regardless of which numbers you look at. This abnormal real estate market is enabled by the Chinese Communist Party’s tight control over land supply, and by a financial system that favors the rich and the connected. In fact, the real estate sector and China’s financial system are closely intertwined, with more than a quarter of outstanding loans in the financial system being related to the real estate sector. This means that China’s banking system is highly exposed to the real estate sector. The fates of the two sectors are now braided together, making them resistant to structural adjustments — a situation not unlike that of Japan’s economy in the 1980s.

China's real estate market is not like the magic beanstalk in the English fairytale, stretching endlessly into the sky until it reaches a cloud castle of riches. The national economy cannot keep growing indefinitely. All bubbles must burst eventually, causing economic shock and reversal of fortune. After three decades of impressive growth, Japan’s housing bubble burst, leaving in its wake two decades of stagnated growth.

If China’s real estate bubble were to burst, the Chinese economy would experience a strong contraction, enduring a long period of stagnation. This would have unforeseen social and political consequences. To fend off such a terrible prospect, the Communist Party has long been been working overtime to delay the bursting of the real estate bubble and avoid painful market adjustments that someday must come.

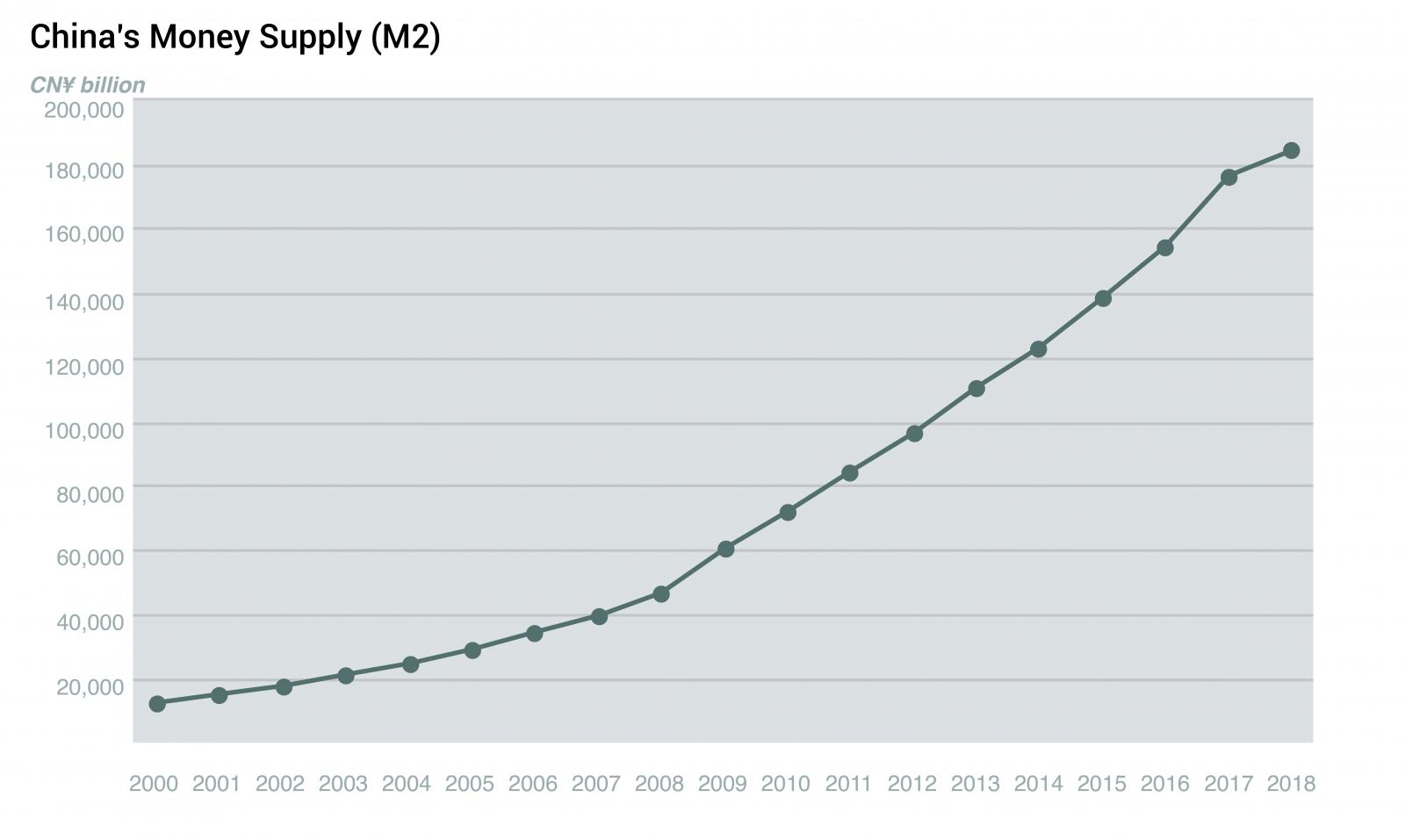

Below is a chart showing the growth in China of so-called “broad money,” or M2, which includes cash and checking deposits, as well as savings deposits, money market securities, mutual funds, and other time deposits. M2 is generally watched very closely by economists as an indicator of money supply and possible future inflation, and as a target used in the monetary policy of central banks.