Image generated by DALL-E AI system.

Local Debts: Whose Baby?

As the local debt crisis in China intensifies, Part Two of our analysis explores how governments at various levels struggle to manage the burden and the future outlook.

Quick Takes:

- Local government debt defaults have already occurred in China, and a debt peak is imminent.

- The central government has persistently refused to bail out localities over the last few years, calling on provincial governments to bear the debts instead.

- Since 2015, provincial governments have increasingly issued credits to replace hidden debts, taking on new debt to pay down the old. However, local debt continues to rise.

- Lower-level governments use creative methods for local finances, such as increasing fines, selling concessions, and delaying payments to private companies, causing disruptions in public services and social risks.

- The central government has had to resort to a series of monetary expansions in 2023 to help lessen the local debt burden, and this will be a major trend going forward.

In part one, the author lays out the underlying mechanisms behind the spike in Chinese local government debt, arguing that this escalating burden was not simply the doing of local officials but a product of the whole debt-fueled economic model pursued by both central and local governments over the last decade or so.

China faces a mismatch in fiscal powers and public service responsibilities between central and local governments, which leads the local governments to employ creative methods to finance various projects; for this purpose, so-called Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) were established to circumvent the budget law and facilitate borrowing. In part two, I will look at how the LGFV debt crisis has manifested, how a tipping point might be reached in the debt crisis, and what countermeasures the various levels of government have available to ward off debt risk.

The form of the Chinese LGFV debt crisis differs from a typical debt crisis: China may see slower-than-expected debt transmission, less intense collapses in asset prices, and shocks to the real economy due to underdeveloped financial markets. We need to sketch out how debt evolves under different sets of assumptions.

Local government debt includes hidden debt, namely bank credit and non-standard debts; a partial default on these triggers will diffuse crises, spillover effects will be weak, and a Minsky moment will not ensue: multiple cities have already experienced debt-servicing issues, whose governments have ordered local banks to roll debts over, and debt restructuring has taken place for suppliers and other financial institutions. Still, an LGFV debt tipping point has not been noticeable from the outside.

On the other hand, if debt crises occur in a more concentrated manner, with significant spillovers, two dangers may occur: firstly, a cashflow crunch for local state-owned banks due to their excessive rollovers, leading to a spike in bad loan ratios and the emergence of systemic bank risk. Secondly, public transport and subways run by LGFVs ceasing service due to cashflow issues, with ensuing social risks; over 20 cities have seen public transport come to a standstill due to insufficient fiscal subsidy since 2022. Moreover, in the face of wage arrears of up to 5 months, striking bus drivers paralyzed public transport in Tai’an, Shandong Province, in August 2023, a type of incident previously almost unheard of in China.

In this author’s view, partial local debt defaults have already happened, and the central government response has been two-fold: provincial governments have borrowed money to reduce debts, and the central government has borrowed to invest; this is due to continue as the primary approach to alleviating debt moving forward.

LGFV Debt Risk

LGFV debt around China currently presents four specific risk factors:

i) High indebtedness: The broad debt ratio of the local Chinese government (outstanding debt as a proportion of overall government finances) and broad liability ratio (outstanding debt as a proportion of GDP) were 320 % and 74%, respectively, the highest levels among major world economies in 2022; broad debt ratio of Tianjin has reached 774 %, and broad-measure debt ratios were over 300% in 17 other province-level entities.

ii) Peak repayment season: 2021-2025 marks a peak period for LGFV bonds reaching maturity, with an annual average of 3.2 trillion-yuan worth coming to term; in 2023, nearly 4 trillion yuan in bonds reached maturity, a historical record; for each of the next two years, it will be over 3 trillion.

iii) Negligible returns: According to Fitch Ratings, The Return on Assets for more than 1,300 onshore LGFV issuers, based on reported results for the third quarter of 2023, dropped from 0.73% in 2021 to 0.57% in 2023.

iv) Serious solvency shortfalls: Bank of China analysis shows that the median tangible assets / interest-bearing debt ratio for Chinese LGFVs was 1.04 in 2021, meaning that it would be necessary to dispose of almost all their tangible assets to be able to – barely – repay all their interest-bearing debt; the ratio of net cash flow from operating activities to interest-bearing debt was only 0.48% in 2021; in other words, the business operations of numerous LGFVs do not produce enough cash flow to cover their debts.

The central government does not allow local government LGFV bonds to be defaulted on in the bond markets; there have been no instances of this so far; their hidden debt, however, is even greater in volume and has occasionally been materially defaulted on; take the example of Zunyi Daoqiao (Zunyi Roads & Bridges), the largest state-controlled LGFV in Zunyi, Guizhou Province, which engages in infrastructure, municipal services, and real estate; Zunyi Daoqiao had 45.754 billion yuan of debt outstanding at the end of June 2022, compared to only 673 million yuan of operating revenue for the first two quarters; Zunyi Daoqiao announced on 30 December 2022 that following amicable and even-handed negotiation with bank-type financial institutions, it was to restructure its bank loans: around 15.6 billion yuan in bank credit would have its term amended to 20 years, the first ten years would see only interest paid and not principal, and the principal would be paid off in the second half of the 20 years. This restructuring only covered the bank credit portion of Zunyi Daoqiao’s debts; the local government managed to leverage its control over local banks to extend the credit as if rolling it over, whereas it was already in serious default; this LGFV had another approximately 30 billion yuan in credit to repay, some borrowed from other financial institutions, some in the form of open-market bonds; by the summer of 2023, as Caixin reported, Zunyi Daoqiao was once again embroiled in a debt restructuring struggle; this example not only shows the impotence of Chinese local banks in the face of political pressure but will also leave markets concerned about spillover effects as more LGFVs go down the same path.

“Your Baby, You Own It.”

With such low solvency levels, whether LGFVs have any chance of avoiding default depends on local governments bailing them out from the public coffers; LGFVs owe their entire existence to helping local governments circumvent the Budget Law to raise funds; their borrowing and credit activities have been carried out on behalf of local governments, and so repayment of their debts must depend on local governments, too; in other words, LGFV debt is effectively local government debt.

LGFVs owe their entire existence to helping local governments circumvent the Budget Law to raise funds; their borrowing and credit activities have been carried out on behalf of local governments, so repayment of their debts must depend on local governments, too; in other words, LGFV debt is effectively local government debt.

Alarmed by the extent of LGFV debt risks in 2021, the central government issued a decree limiting their expansion, calling on localities to proactively mitigate and convert their accumulated hidden debt to explicit debt; the Ministry of Finance’s refrain in the middle of 2023 was “your baby, you own it”: there would be no central government bailout, with provincial governments instead expected to shoulder the debt burden of their local governments; only seven province-level entities, however, fulfilled this debt relief mission in 2022, and only Guangdong Province and Beijing Municipality reduced their hidden debt to zero.

It never rains, but it pours, and there was a major fall in local government fiscal revenue in 2022 when only 8 of 31 province-level entities of China posted positive fiscal revenue growth; research shows that if local government fiscal surpluses are added to local State-Owned Enterprise profits (including those of LGFVs), the amount arrived at is only the equivalent of 2.18% of overall local debt, not enough even to repay debt interest.

With debt relief being this impossible, pressure to repay has led to a certain amount of buck-passing; a post on the Guizhou provincial government website drew attention in April 2023, stating as it did that due to limited financial resources, it is difficult [for local governments] to carry out debt relief, and an effective solution cannot rest on their capabilities alone. It was a rare public call for help from the central government that demanded actionable advice although the post was subsequently taken down. A post in June that year on the official website of the Guangxi Autonomous Region called on LGFVs to clear and dispose of debts themselves, and ruled out the government shouldering this responsibility.

Lower echelons of government have racked their brains for ways to deal with debt; they have shown considerable creativity; firstly, they have done everything possible to diversify sources, such as by increasing revenue from fines and asset seizures. Compared to 2014-2017, the local government fines and seizure ratio (revenue from fines and seizures as a proportion of fiscal revenue) rose considerably in 2019-2022, with 11 province-level entities showing rises of over 50%; Tianjin Municipality, for example, raised 13.5 billion yuan from these in the former period, increasing to 36.4 billion yuan in the latter.

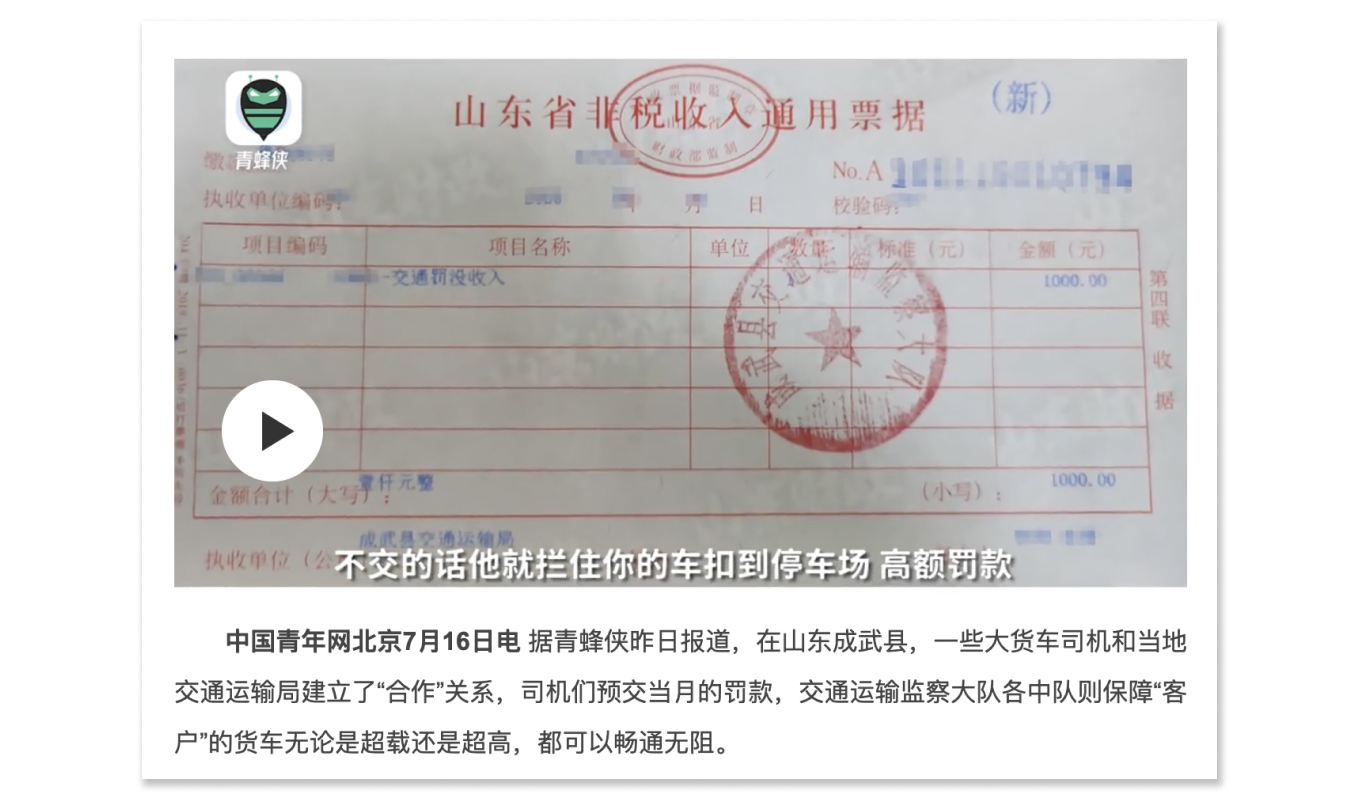

An elderly streetside vegetable seller in Luoyang, Henan Province, was fined 110,000 yuan in 2023 because his produce was not up to standard; he had only made a ¥21.05 profit from it; the Public Security Bureau of Chengde, Hebei Province, seized a local programmer's entire three-year income, 1.058 million yuan, for the sin of having used a VPN (Virtual Private Network); the fine and seizure income of the city was 990 million yuan in 2022, 13.1% of total fiscal revenue. A traffic camera at an expressway junction in Foshan, Guangdong Province recorded a total of 620,000 traffic offenses since its installation in 2020, media reported in 2021, raising a total of 120 million yuan in fines; the transport department in Chengwu County, Shandong went as far as to promote a monthly fines pass scheme by which truck drivers could prepay their fines for the month, which gave them carte blanche to overload their trucks.

Screenshot from a video on https://news.youth.cn, showing a Shandong Province non-tax revenue receipt received by a truck driver after purchasing a monthly fine pass; the driver claimed that if he refused to buy the pass, the local transportation authority would confiscate his truck and impose significant fines.

Local governments have also been maximizing returns from state assets in their jurisdictions, typically by offering banks long-term operating rights for these assets as loan collateral; Langzhong City in Sichuan is reported to have auctioned off 30-year concessions for the canteens in its schools and administrative bodies; elsewhere in Sichuan, the tourist destination of Leshan raised 1.7 billion yuan from auctioning off a 30-year vending stall and sightseeing bus concessions at its Giant Buddha complex; Rongjiang County in Guizhou sold off a 20-year concession to operate its crematorium.

Public parking space concessions have become a new nationwide bonanza since 2022; nearly all roads in Nanning, Guangxi province, have had paid parking spaces marked out along their length, media reported in 2023; parking fees are high, and even bicycles get charged; Huibo Parking, a state-owned company, operates these parking spaces; the company paid 2.5 billion yuan for a 25-year concession and subsequently pledged that concession to banks as collateral for another 2 billion yuan in credit; it also signed a Cooperation Memorandum with a local court, which provided them with a litigation fast lane to pursue unpaid parking fees.

When it comes to individual and private company creditors, local governments have typically adopted a delay, pass the buck and hide strategy, the former holding little chance for redress in the face of the latter’s administrative power; overdue payments to private enterprises by governments and state-owned enterprises in Henan Province alone increased by nearly ten billion yuan in 2022. In turn, these private companies often owe wage arrears to migrant workers; a construction company complained online in 2023 that they had taken on a road-building project in an industrial park in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in 2012, for which they had advanced all the upfront costs themselves but, nearly ten years after completing the works there were still close to 15.4 million yuan of project costs and migrant worker wages owed; only the weight of public opinion ended up swaying the local government to commit to paying off the arrears within five years.

The central government has specifically ordered local governments and SOEs not to delay due payments to SMEs for goods, works and services; the latter’s weak bargaining position and the enormity of local debts, however, mean that local government arrears to businesses have remained considerable. Businesses have sometimes been forced to accept haircuts on what they are owed before getting paid; a listed environmental technology company in Jiangsu Province announced on 26 October 2023 that it had reached a debt restructuring agreement with two local government departments in Yunnan Province for over 163 million yuan owed by the latter, under which they expected to recoup only 121 million; the local governments were effectively getting a 26% discount.

New Loans to Repay the Old; More Relief Leads to More Debt.

In light of the above, looking at local governments alone (particularly city and county-level ones) does not offer realistic prospects of relieving China’s crushing local debts. A debate is still raging in China over whether to break with the current rigid approach to defaults and allow heavily indebted LGFVs to go bankrupt, as LGFV defaults would essentially mean the local governments in question lost all creditworthiness; after a local debt crisis occurs, the local government will face enormous challenges in getting further financing on the debt markets, and provincial and central governments will no longer be able to sit on the sidelines.

The Chinese fiscal system is a typical example of heavily centrally concentrated power; following the 1994 tax-sharing reform, there has been a mismatch in fiscal powers and public service duties between central and local governments; local governments have excessively high public spending responsibilities, whereas the central government has taken the ‘crown jewels’ of local tax revenue for itself, part of which they then redistribute to less well-off provinces using transfer payments; there is a strong link between local fiscal balance sheets and central fiscal powers – the two are inseparable.

It must be reiterated that there is a significant structural issue with Chinese government debt and that debt and credit are mismatched: the creditworthiness of local governments is relatively low, but their debt levels and ratios are high; the debt leverage ratio of the various echelons of local government now averages 78%, the highest among major economies worldwide; the equivalent figure is below 30% in the USA and Germany, and under 10% in France and the UK. Meanwhile, the credit of the central government is impeccable, but its debt amounts to only 26 trillion yuan, and its leverage ratio is only 21%, far below the US Federal government with 120%.

The central government became aware of the risks of out-of-control hidden debt as early as 2014; it passed a new Budget Law on 1 January 2015 allowing provincial governments to issue ordinary and special bonds. Now, provincial governments with better credit can issue their debt and reduce dependence on LGFVs, rebalancing the structural mismatch while they mitigate risks by replacing hidden with explicit debt.

Unfinished buildings in Guangdong. Photo for Echowall by Liang Shixin.

The first round of China’s debt relief policy took place from 2015 to 2018 and mainly involved provincial governments issuing replacement bonds to replace the stock of hidden debt. During this round of debt replacement, standardized government bond issues were encouraged, and the interest burden of the local government was cut by something in the order of 1.7 trillion yuan. On the other hand, the upward trend in total local government debt was not curtailed; indeed, while explicit debt (ordinary and special bonds) saw significant growth, new LGFV debt also continued to mushroom, reaching 47 trillion yuan total by the end of 2020, up 176% on 2014.

Debt relief through debt replacement was launched in 2020 for the second time. Provincial governments started issuing refinancing bonds at scale, mainly to repay explicit debt that had come to term. However, local debt grew.

With the disappointing post-pandemic recovery in the first half of 2023, fiscal revenue fell; in particular, revenue from leasing the state land - the cash cow of the local government dropped 21.3% year-on-year. The proceeds of state land lease transactions for 2023 are estimated to reach around 40% of their level in 2021. In the face of this economic downturn and the ensuing rise in debt risks, the central government has not strayed from its macroeconomic policy; its stance towards bailing out local debt remains opaque; despite plummeting confidence in the market, policy interest rates have not been proactively cut; thus, market interest rates and debt repayment burdens have gone up in real terms; the local debt crisis continues to worsen, and the window for a rescue continues to shrink.

The above two rounds of debt relief saw local government debt levels stubbornly climb as the explicit debt of provincial governments and hidden LGFV debt continued to grow strongly. Why would this be?

Soft Budget Constraint

The Hungarian economist János Kornai introduced the concept of soft budget constraint, which is often associated with economic behavior in socialist and transition economies. It describes a situation where entities face little to no consequences for their financial decisions and are, therefore, able to borrow money without the pressure of repayment. This lack of accountability fosters inefficiencies within the economy.

The debt and credit mismatch engineered by asymmetric central and local fiscal and government service remits is the surface manifestation of a much deeper issue: one of the least market-oriented areas in China is the financial system, with obvious symptoms of soft constraints on government budget and debt. While the Budget Law regulates the explicit debt issuance by provincial governments, there is no independent judicial oversight of fiscal revenue and spending or debt issuance and repayment. Moreover, there are not enough hard constraints on banks or pricing constraints in the form of freely set loan interest rates. LGFV debt is even more problematic, lacking a binding legal framework and rigid pricing constraints.

Localities Borrow to Pay the Debt; the Central Government Borrows to Invest.

A meeting of the Politburo Central Committee in July 2023 laid down a clear line: Local debt risks must be effectively warded off and mitigated, and a debt relief package drawn up and implemented, signaling the beginning of a third round of debt relief operations. The debt relief package includes debt replacement, reorganization, and rollovers; as the past two rounds, the emphasis is on the first of these measures. A flurry of special refinancing bond issues by provincial governments in 2023, totaling over 1,5 trillion yuan, aimed to pay down their outstanding local government debts; nevertheless, as analyzed in a report by SP Global Rating end of 2023, this figure falls below half of the 4.4 trillion yuan LGFV bonds maturing from October 2023 to December 2024. It seems even more modest than the outstanding bond balance of 49 trillion yuan as of the end of 2022.

When there is not enough fiscal revenue to repay debts, local governments must take on new debts to repay the old, keeping their debts rolling over.

Why have all three rounds concentrated on debt replacement? When there is not enough fiscal revenue to repay debts, local governments must take on new debts to repay the old, keeping their debts rolling over. Bond issuance data estimated that local governments had total outstanding bonds of around 8 trillion yuan in the first three quarters of 2023; new bond issuances made up 4.3 trillion yuan, of which 3.97 trillion were new bonds taken out to pay old ones; in other words, rollover bonds accounted for around 50% of total debt issuance and made up 92% of new bonds.

The logic behind debt replacement calls for (1) exchanging low-rated debt for debt with higher credit ratings; i.e., provincial governments issue bonds to replace hidden debts of the county and city-level governments; (2) using low-interest debt issued by provincial governments to replace the current high-interest debt; and (3) replacing short-term debt with long-term debt, which defers repayment pressures. In 2022, local government bonds had an average term of 13.2 years, 1.3 years more than the previous year.

Debt relief will remain a main task for provincial governments for several years. That said, now that local governments have the task of taking on debt to relieve debts, their creditworthiness and room for financing will erode; their investment levels will thus fall; the Chinese economy and government rely heavily on public investment, which means the central government will have to increase its debt issuance to pick up the investment slack.

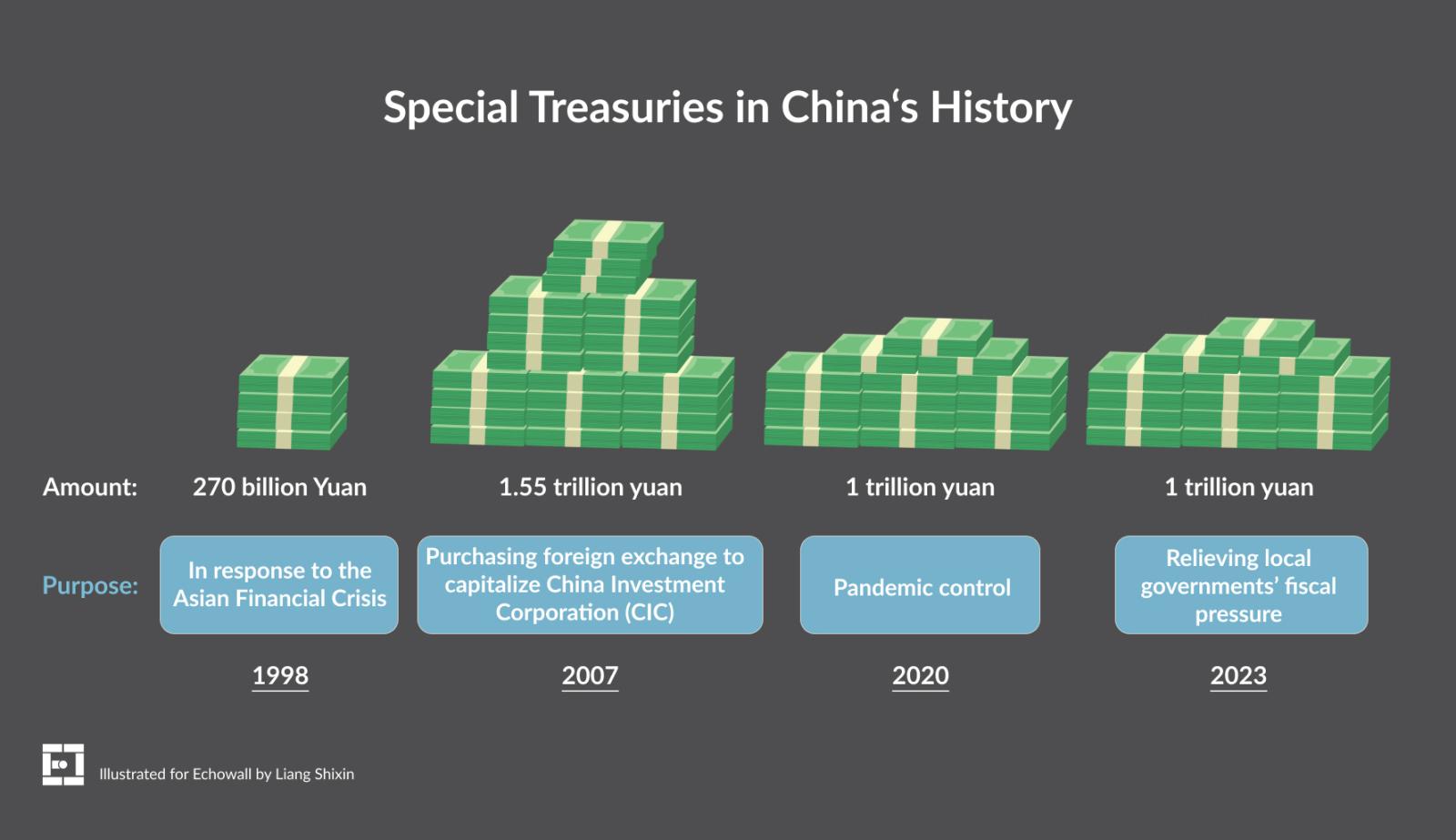

The central government announced on 24 October 2023 that it would issue one trillion yuan more in special Treasury bonds in the fourth quarter of the year, 500 billion yuan would be used within the year, the proceeds all going to local governments via transfer payments and mainly earmarked for flood relief, flood control and other infrastructure; to the markets, this was odd news since China had only issued special Treasuries three times beforehand, each time for a special purpose: the first was during the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis, the second was a 1.55 trillion yuan issue in 2007 to purchase foreign exchange to capitalize CIC (China Investment Corporation). The third occasion was a 1-trillion yuan special Treasury issue in 2020 for pandemic control purposes. There is nothing special in character about the problems China faces in 2023, though - certainly no more so than beforehand.

Furthermore, flood control and prevention infrastructure investment in the past was under local LGFV financing and the general central public budget, without the need for recourse to special Treasury bonds. The purpose of the central government special Treasuries issue in 2023 was to compensate for the lack of investment from local governments; the proceeds are being passed to local governments via transfer payments, relieving some of their fiscal pressure and creating an economic stimulus via infrastructure projects.