A Chinese astronaut holding a cell phone with a green health code. Illustrated for Echowall by Liang Shixin.

Old Regime, New Tech

The technology behind China’s COVID-19 apps is neither homegrown nor cutting-edge, while pandemic response across the country still relies on the old governance model of social control through immense manpower.

Quick Takes:

- Technologies behind Chinese COVID-19 apps are not cutting-edge and China’s data surveillance is accompanied by the all-encompassing governance system with immense manpower to control the population.

- To mobilize the fight against the pandemic, the official discourse uses class struggle language, which in practice leads to exclude particular individuals and groups from the definition of the “people” or the “us”.

- For fear of losing their career, local officials are vying to invent the most stringent control measures to show political will, rather than weighing up public health or the public interest.

“Did they have the green health code for entering China?” When three Chinese astronauts returned to earth this September after a space mission, Chinese internet users ironically posted this question.

Having been the first to bear the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic, China also turned out to be the earliest adopter of surveillance technologies in response. Since early 2020, localities around China have rolled out a smorgasbord of health-related QR codes that citizens need to carry and show, with many everyday activities now off-limits for anyone lacking a so-called “green code” confirming that they’re healthy.

The central government laid down “zero-COVID” (清零) as an overarching objective and China’s enduring success in keeping infections close to zero has attracted many a curious eye to its pandemic governance model. A key narrative lens many have seen China’s accomplishment through is its use of cutting-edge technology. Harvard Business Review, for one, saw lessons to be learned from Chinese tech giants - its argument being that “the COVID-19 crisis […] has demonstrated the effectiveness of these models in China.” Many who study politics, though, see in China’s surveillance technologies the early onset of an Aldous Huxley-esque scenario, and fear China will export a new model of digital (or technological) authoritarianism globally.

Whether in admiration or horror, most Western takes have honed in on the leading and efficient technology employed by the party-state, such as in this CSIS (Centre for Strategic & International Studies) commentary:

"The combination of retreating US leadership and the COVID-19 pandemic has emboldened China to expand and promote its tech-enabled authoritarianism as world’s best practice. The pandemic has provided a proof of concept, demonstrating to the CCP that its technology with ‘Chinese characteristics’ works, and that surveillance on this scale and in an emergency is feasible and effective."

Through my own experience of being subjected to China’s “health codes” and my long-term familiarity with the country’s tech ecosystem, the author of this piece will venture a different conclusion in response to the nation’s use of surveillance tech: China’s pandemic control is still rooted in the old regime, out of which the following question begs to be asked: if new technology is used in furtherance of old governance models, whose interests does all this improved efficiency actually serve?

If new technology is used in furtherance of old governance models, whose interests does all this improved efficiency actually serve?

Low-Cost Tech, High-Cost Manpower

China's COVID-19 ‘health code’ (健康码 jiankang ma) was invented, so the official media narrative goes, by a Hangzhou police officer called Zhong Yi. Hangzhou is a national pilot city for the Ministry of Public Security’s Smart Cities and Big Data strategy. Zhong Yi himself is deputy head of sector for technology, informatization and computer application management at the Hangzhou Public Security Bureau, and was involved in developing a police surveillance system called The Urban Brain (chengshi danao) that amasses 15 billion data entries per day. Zhong and his team took only 3 days after the city’s first coronavirus case in February 2020 to develop an application that became known as the Hangzhou Health Code.

Screenshot of a People’s Daily video on Zhong Yi and the invention of the Hangzhou Health Code. The slogans on the right read: “Beating Crime”, “Maintaining Safety”, and “Serving the People”.

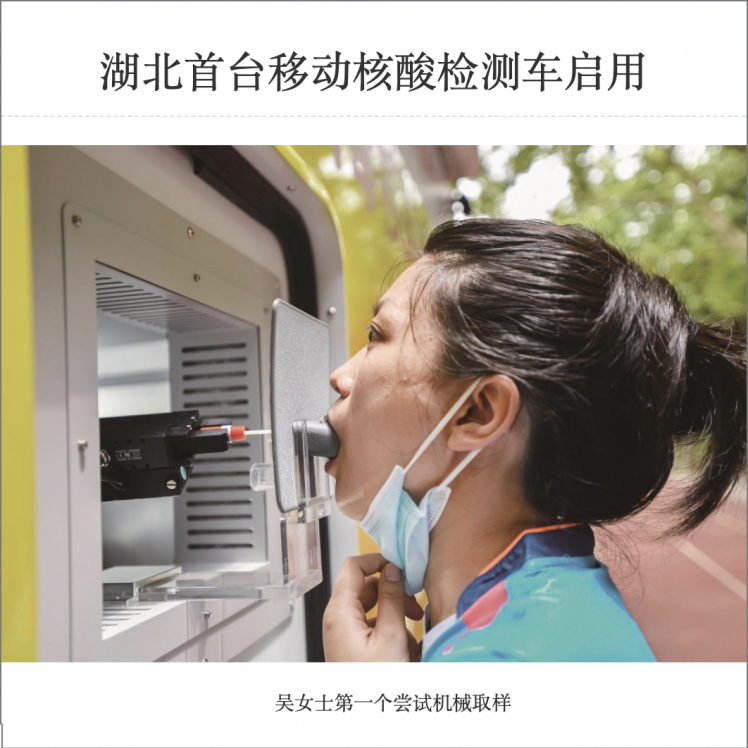

The technology behind it wasn’t homegrown, but is simple enough: rapid collection of geolocation information on citizens’ movements, used in turn to track the spread of diseases and monitor the range of citizens’ activities. Geolocation is possible via the Call Detail Record (CDR) data accumulated by the all three cellular networks (China Mobile, China Unicom, China Telecom); when a local Chinese resident uses their phone, its signal location is picked up by this Big Data network. When there are no ongoing coronavirus cases, the system displays a green QR code. When an outbreak occurs, the authorities designate certain areas as medium or high-risk, and health codes turn orange or red for whoever lives, works in or transits those areas, the consequences of which include follow-up investigations and coronavirus nucleic acid tests (NAAT).

The health code app asks for the citizen’s name, ID card number, photo, address, contact details, personal movements in the last 14 days, any diagnoses such as fevers, any contacts they’ve had with potentially infectious persons, and even other personal data such as the legal representative of the company they belong to. After the citizen fills in this information, the authorities ask them to enable data cross-checks via their cellular operator. Other people can sometimes be added to the user’s mobile app such as elderly people or children who lack their own phones or ID cards.

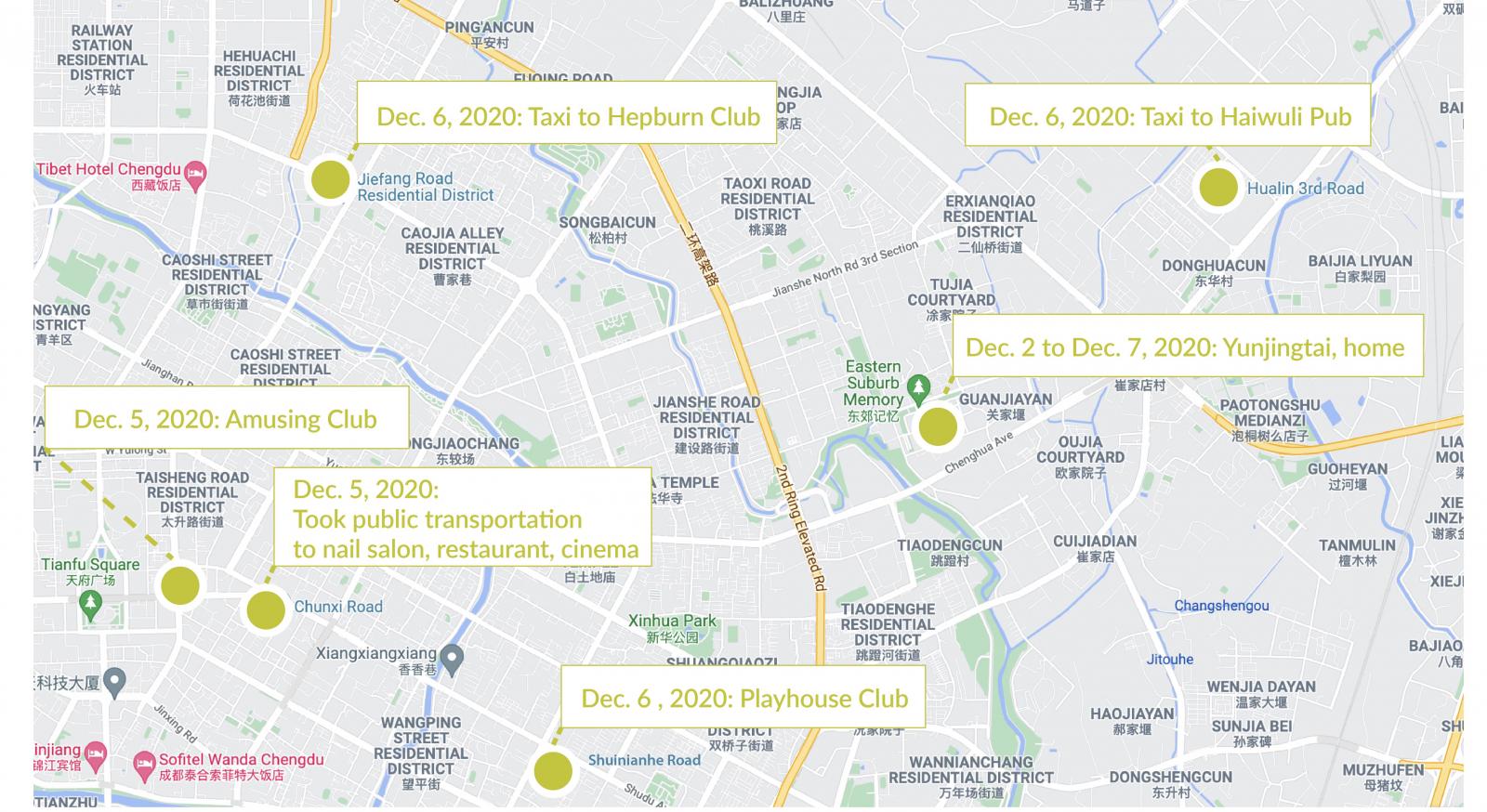

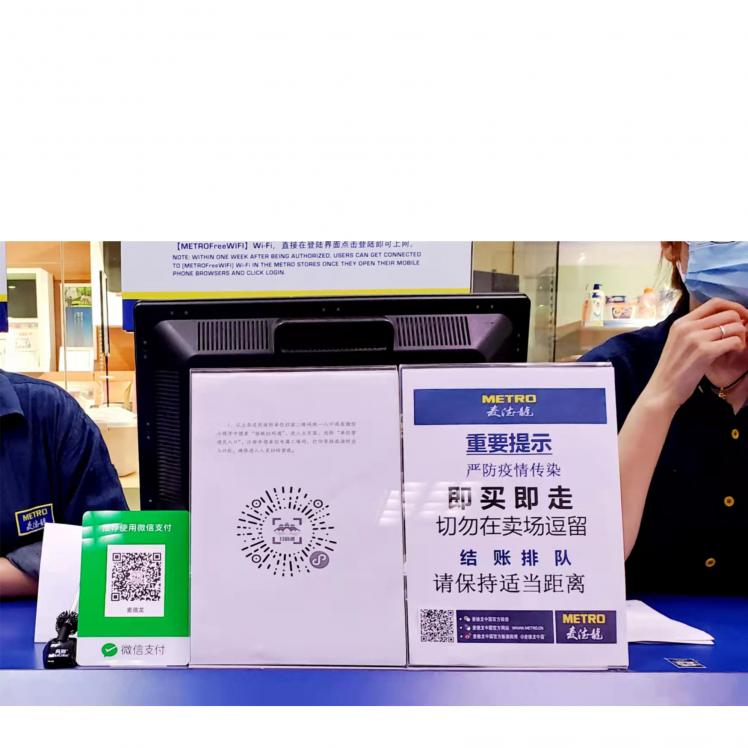

Access to all public spaces in China such as shops, hospitals and public transport now requires a green code. These spaces typically display a QR code at the entrance, which customers are required to scan with a mobile app loaded with their personal data, at which point staff members’ phone screens will show if they’ve been in a medium or high-risk zone or if they’re close contacts of someone who has been ordered to isolate, and the staff member can immediately assess their “security grade”. The government has cloud access to these QR code scan records and can track everyone’s movements in public places, so that when an outbreak happens, they can carry out rapid epidemiological tracing and impose isolation and NAAT testing on the people in question. The Big Data scan records of people’s access to public places are uploaded to a government cloud server which can monitor hundreds of millions of people’s potential threat on a 24-hour basis. This “grid-style” surveillance covers not only individual’s daily health situations, but also their movements and activities.

Some years back, as life was becoming more data-heavy, the Chinese government rolled out various surveillance measures. A ‘real-name registration’ requirement was instituted for SIM cards, social media accounts, courier deliveries and online shopping. The Network Security Law took effect on 1 June 2017; Article 24 stipulates that network operators must require users to provide verified identity details. “Where the user does not provide their genuine ID data, the network operator must not provide relevant services to them.” This legal provision is generally seen as the bellwether for across-the-board network user verification in China.

Network surveillance, however, used to only be done online. It was the 2020 pandemic that expanded this government surveillance into real-life activity. Health codes have grown into China’s largest current O2O (online to offline) data collection funnel, used to monitor people’s movements and circulation.

At the other end of this funnel is China’s all-encompassing governance system. More than 500,000 village committees, 100,000 residents’ committees, and 8000 neighborhood offices (jiedao banshichu) combine to form the front-line units of an enormous multi-tier social governance process. These government staff have been entrusted with making the rollout of health codes happen.

Access control in a Metro supermarket in China. Customers have to scan the QR code before the entrance. Photo by the author.

There are 6 million chain supermarket sites in China and seldom is a street corner without one of the country’s 110 million small retail outlets – corner shops, fruit shops, hairdressers. Unlike ID card scanners, which are expensive and take long to produce, health codes are obviously a low-cost measure which can be rolled out quickly nationwide. The retailer just needs to fill out a simple application to get their own specific health code, which can be printed on half a sheet of A4 paper and pasted at the entrance for customers to scan while entering. It falls to neighborhood offices, a community-level government entity, to verify the address data for the health code; send out staff to carry out awareness-raising and censorship, and ensure there is a health code displayed at every public space where transmission of the virus could possibly happen. Meanwhile, staff from residential communities are expected to question and record the details of citizens coming in and out, and make sure that no ‘issues’ occur in their particular residential zone.

It is to be stressed that pandemic control at the local level across China has employed a combination of data surveillance and human screening, with the aim of ensuring zero transmission.

For example, after an COVID-19 outbreak in Guangzhou in May 2021, the city set health codes to yellow for all persons who had passed through certain “key zones” or “key sites” and demanding that they obtain three consecutive negative results from NAAT tests over two days before they could get their green code back. (ChineseCenter for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) rules designate several dozen venue types including docks, shopping centers and sports stadia as “key sites”). Guangzhou police officers were also sent to carry out spot checks, searches and tracing to find details of how the outbreak happened.

Examples of the different colors of the Guangdong Health Code on the official website of the Guangdong government.

Medium and high-risk zones in Guangzhou were placed under sealed-off “grid-style management”. This included residential compounds which had seen at least one COVID-19 case (medium-risk) or more than 10 cases over 14 days or at least two concentrated outbreaks (high-risk). Residents of these sealed-off compounds were forbidden from leaving their homes, all businesses and other venues were ordered closed, and there was repeated community-wide NAAT testing. Police, judicial, and neighborhood authorities carried out 24-hour monitoring of the home isolation orders imposed on residents in these zones. For example, after 6 locally transmitted cases occurred in Guangzhou on 3 June of this year, 140,000 people were placed under stay-at-home orders, and could only get food supplies by ordering online or relying on government distribution. Guangzhou also applied a “trio” grid management approach, putting one community volunteer, one police officer and one medical professional together into groups. These “trios” were required to visit every single household in the sealed-off compound(s) and their tasks included order and stability, community surveillance, medical services, health monitoring, taking nucleic acid test swabs, and personnel micromanagement. A month after Guangzhou’s outbreak, the city had deployed a total of 60,000 police officers and over 10,000 “trios” to carry out community surveillance and verify epidemiological details.

This social-control-at-all-costs model has come at a vast price in terms of human time and physical resources, and it is difficult to reach a rational reading of its efficiency and public benefit calculus. For example, after an outbreak in the city of Nanjing in July 2021, 7 rounds of city-wide mass testing were carried out equating to 40 million NAAT tests, which unearthed a grand total of just 233 positive results. Being the provincial capital of Jiangsu, Nanjing was able to get other cities in the province to send medical staff and physical resources, unlike the nearby city of Yangzhou which saw a concentrated outbreak occur at a testing station with at least 50 people infected while queuing for their tests.

The Class Struggle Mentality

Since the COVID-19 epidemic started, a war-like official narrative has dominated the public discourse about it. Take just one People’s Daily editorial from August, entitled “The fight against coronavirus is forging a new psychological milestone for national rejuvenation”(抗疫斗争铸就民族复兴新的精神丰碑), which claims, “Party, army and all ethnicities nationwide are joined as one in an all-out effort, employing the strictest, most comprehensive and most thorough anti-virus measures, sounding the clarion call for a people’s war, a total war, a blockade war against the epidemic.”

The real-life impact of the barrage of war mobilization slogans is that it is not the invisible virus itself but the actual, infected or potentially infected people who become the focus of the battle. “One slogan is as good as ten bullets,” an essay from the PLA National Defense University states, going on to say, “in the struggle against COVID-19 pneumonia, there are slogans adorning village walls, city LED displays, taxi screens, banners on pedestrian bridges, and advertising hoardings in metro stations. Discussing pandemic-related slogans is an important barometer for our success in propaganda mobilization in the digitized war of the future.” The article goes on to cite a widely used slogan as a successful piece of propaganda: “every person who keeps quiet when they get a fever is a class enemy lurking among the people.”

With this kind of class war framing, health code data serves to exclude particular individuals and groups from the definition of the “people” or the “us”. And the former are sometimes not even infected, for example natives of Hubei province, where there was the earliest coronavirus outbreak in spring 2020; many Hubei natives suffered prejudice, discrimination, forced home isolation or evictions when they travelled for business, took up jobs elsewhere, or just returned to where they normally lived in other parts of China – all despite having green health codes from Hubei province.

Pandemic control slogan in Tongzi village, Badong, Sichuan Province: “Every Hubei returnee who doesn’t report to authorities is a ticking time bomb”