The site of the incident on the Meizhou-Dabu Expressway. Photographer unknown.

Those Who Have Disappeared (Again): Emergency Response in China

Highly exposed to severe disasters, China intertwines its emergency relief approach with maintaining political stability and social control.

Quick Takes:

- From 1949 to 1978, disaster governance in China prioritized politics: the government controlled everything, rejected international aid, and tightly controlled information, resulting in unknown death tolls in many disasters.

- After 1978, disaster management shifted towards a multi-stakeholder model, and citizens' engagement emerged following the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake.

- Since 2013, disaster governance has become part of the national security regime, with increased centralization; the party leads emergency response directly while the government conducts implementation.

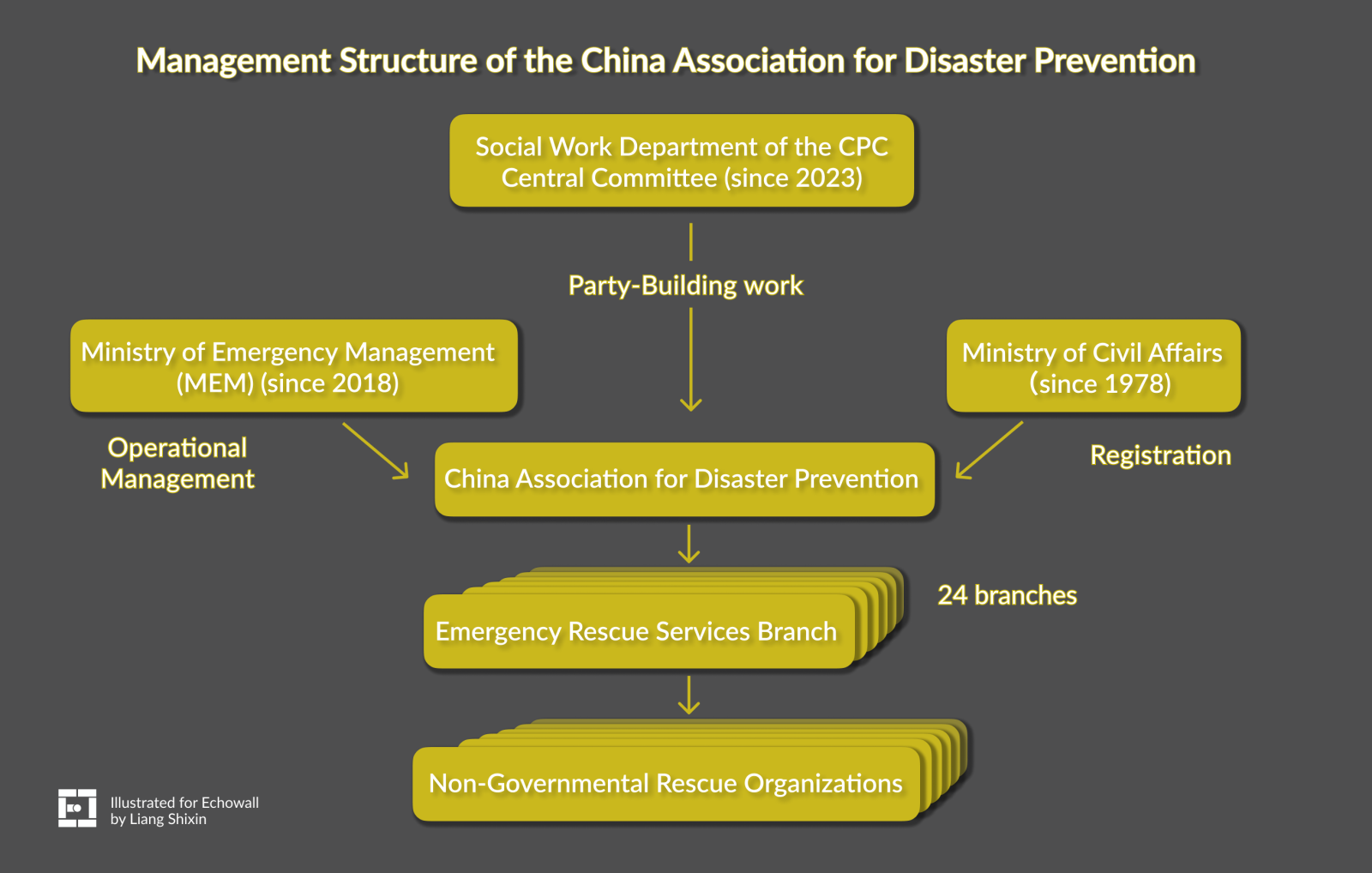

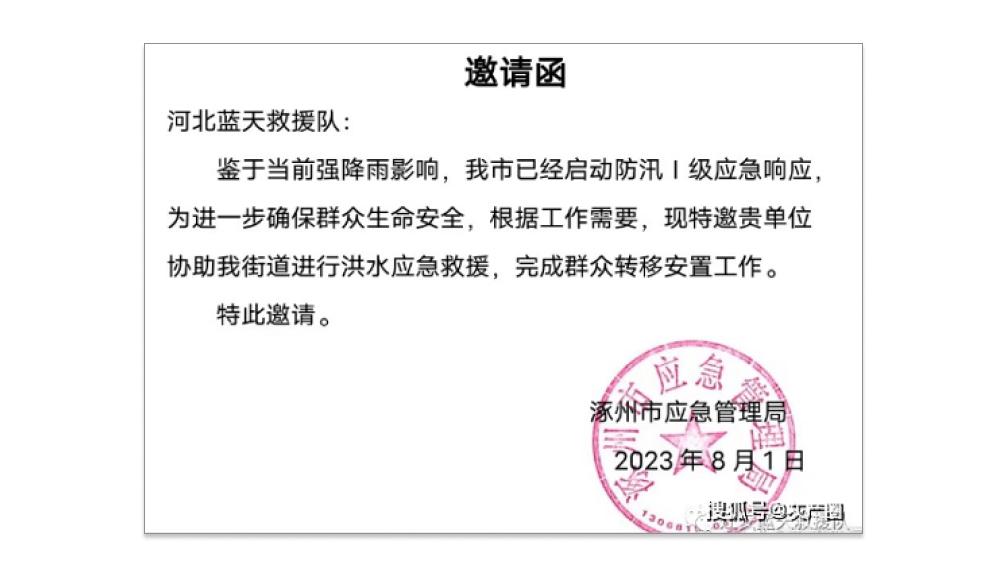

- NGOs are incorporated under associations or as government-purchased services, with strengthened party control, reducing their independence and ability to respond to disasters.

- Journalists can hardly report on disasters, and even central media outlets face increasing censorship and harassment, leading to a decline in transparency, public trust, and societal resilience.

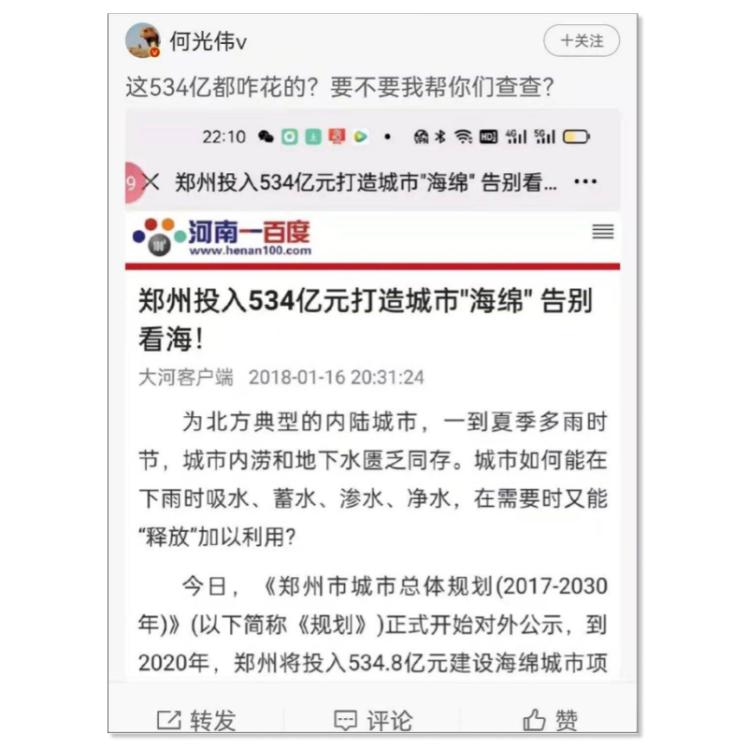

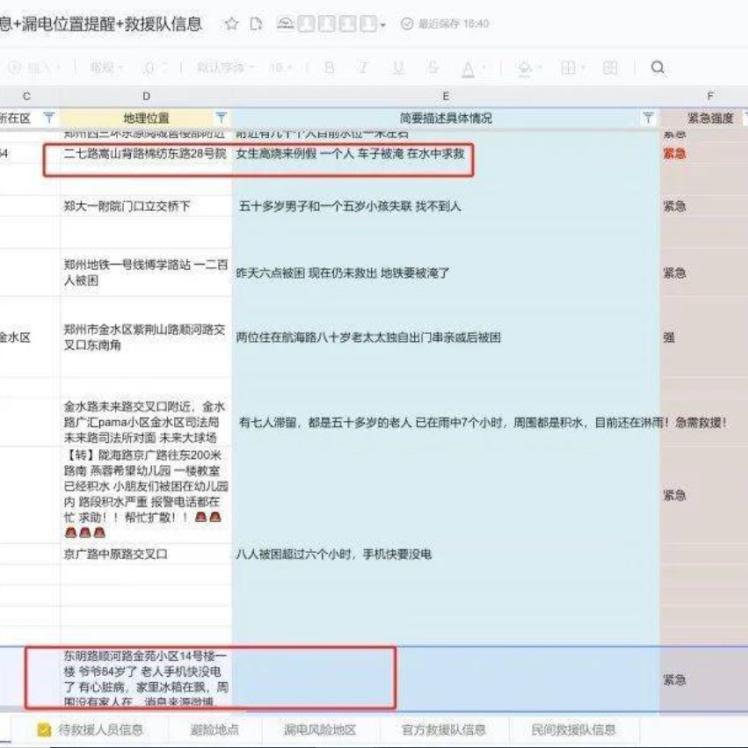

A section of the Meizhou-Dabu Expressway in Guangdong Province collapsed without warning on 1 May 2024. 23 cars rolled down a slope off the highway, with many of them exploding or catching fire. At least 48 died and 30 were injured. Guangdong experienced extreme rainfall in the days leading up to the tragedy. However, it is uncertain whether human factors played a role in the incident, as the public has been unable to access any information on this matter. As law professor Lao Dongyan from Tsinghua University commented on Weibo, a popular social media platform: “Public incidents are getting increasingly difficult to get to the bottom of. We don’t hear about major incidents anymore. Guangdong had just had a whole month of extreme rainfall. Beyond the natural factors, though, the human factor at play with this tragedy has not been investigated. The victims have disappeared from the public sphere.” To this day, the identities of the deceased have not been disclosed.

An article published by Sanlian Life Weekly on May 6, which interviewed individuals connected to the incident, was removed from the internet just two hours after its release. A subsequent article by Caixin, published on May 10, interviewed survivors and construction experts anonymously and raised doubts about the quality of construction of the expressway, which was built during a 2014-2015 infrastructure boom. Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) were frequently used to finance such projects. Meizhou's deputy mayor, who was in charge of the transportation portfolio, was arrested for corruption and bribery in 2023. The Caixin exposé, too, was quickly taken off the internet.

A 404 error message from the Caixin website stating that the page does not exist or has been deleted.

In recent years, China’s approach to disaster management has been “keeping political stability.” In the aftermath of an incident, local authorities quickly dispatch police to seal off the affected area, only allowing access by government-approved media, and “physically isolate” the victims’ families by asking them to stay in hotels and avoid contact with journalists. A rare “free window” after the Meizhou-Dabu Expressway disaster was enough for the Sanlian Life Weekly journalist to find out about the victims from online platforms. Nevertheless, the news article disappeared shortly after the incident, and the victims’ names vanished again, making it impossible to establish a support network involving social organizations and the public.

Disaster relief has been closely linked to political power in China since ancient times, ranging from the legend of “Dayu controlling the floods” to the constant emphasis put on how well the national system ostensibly works in the current era. The narrative focuses on disaster-related achievements toshowcase the capacity of those in power and boost their legitimacy, whereas individuals affected by the disaster are largely ignored.

In recent decades, the relationship between China’s party-state and society has undergone dynamic changes, with increased enthusiasm toward the involvement of civil society in disaster relief and public welfare. However, control strategies, adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic, have once again shown the government’s controlling nature and desire to keep a lid on the public sphere overall. By exploring China’s political context, from the perspective of emergency response, we can get a glimpse of how the power structure has shifted and how autonomous civic participation in public welfare efforts has been nipped in the bud. In this article, I will explore post-1949 changes in the emergency management system, the differences in the government's intention behind disaster relief in different periods, and the resulting social impacts.

1949-1978,“Unified” Management

After 1949, China was governed by a unified management model in which the government exercised control over all aspects of life. Emergency rescue work can be characterized by “foregrounding politics, with the Party and the Government taking over everything and mobilizing the masses to help themselves and rejecting international assistance.” The social space for non-governmental organizations was stifled by an approach that placed the Party at the center of everything: traditional private charities such as Shantang benevolent associations were all banned or transformed. The few remaining social organizations operated as extensions of the Party.

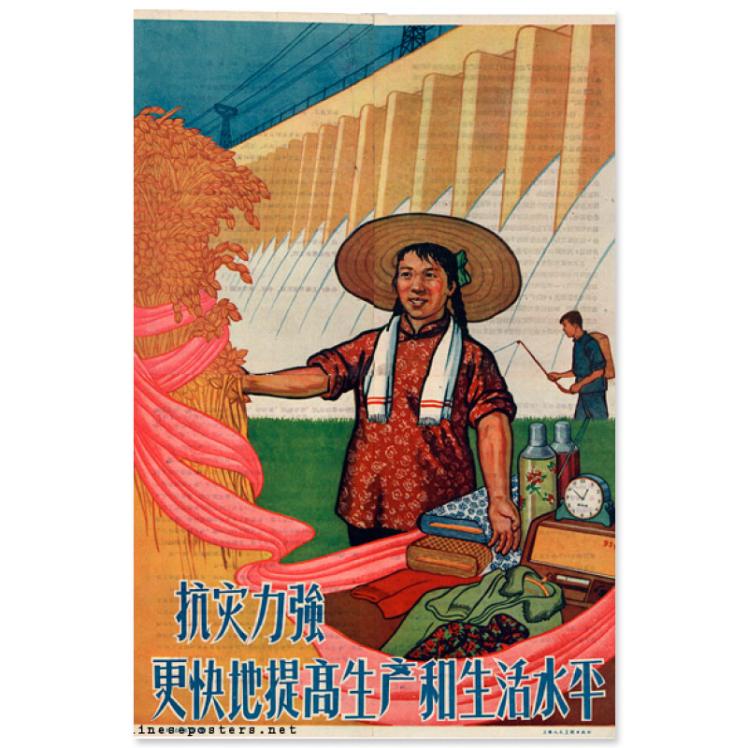

Poster No. 9 from the series "People's communes are good", 1960. The Chinese characters read: "The power to fight disasters is strong to quicker raise the levels of production and life." Image from www.chineseposters.net.

This approach to managing crises prioritized strict information control, as evidenced by the Great Famine (1959-1961): by the end of 1960, large numbers of people had starved to death in rural China, causing the population to fall by 10 million in just a year. A People’s Daily headline on 29 December, on the other hand, claimed that “China’s Agricultural Production Suffered a Severe Natural Disaster in 1960, and 600 million People Overcame, with Full Confidence, the Serious Difficulties” without the article mentioning any death toll at all.

Similarly, on January 5, 1970, after a 7.7 magnitude earthquake in Tonghai, Yunnan province, the only disaster report published in the People’s Daily provided no information about the magnitude or casualty count. The earthquake zone was even euphemized as an area south of the provincial capital, Kunming. Relief sent to the quake zone included hundreds of thousands of copies of The Quotations of Chairman Mao and Chairman Mao badges. Journalists were denied access, only photography by scientific workers was permitted, but only objects were allowed to be photographed, not people. These rules were also applied in the wake of the 1976 Tangshan earthquake. It was not until the thirtieth anniversary of the Tonghai earthquake that the casualty count was released: 15,801 deaths.

In 1975, a devastating rainstorm in Zhumadian, Henan province, resulted in the bursting of two large reservoirs and numerous smaller ones. The ensuing flood caused a death toll exceeding 26,000. The exact death toll from this flood is unknown and should include deaths from infectious diseases and famine directly caused by it. Some studies have called this “by far the world’s worst dam disaster” “As many as 230,000 people may have lost their lives to this catastrophe, yet for two decades it was successfully airbrushed from history by the Chinese authorities.”

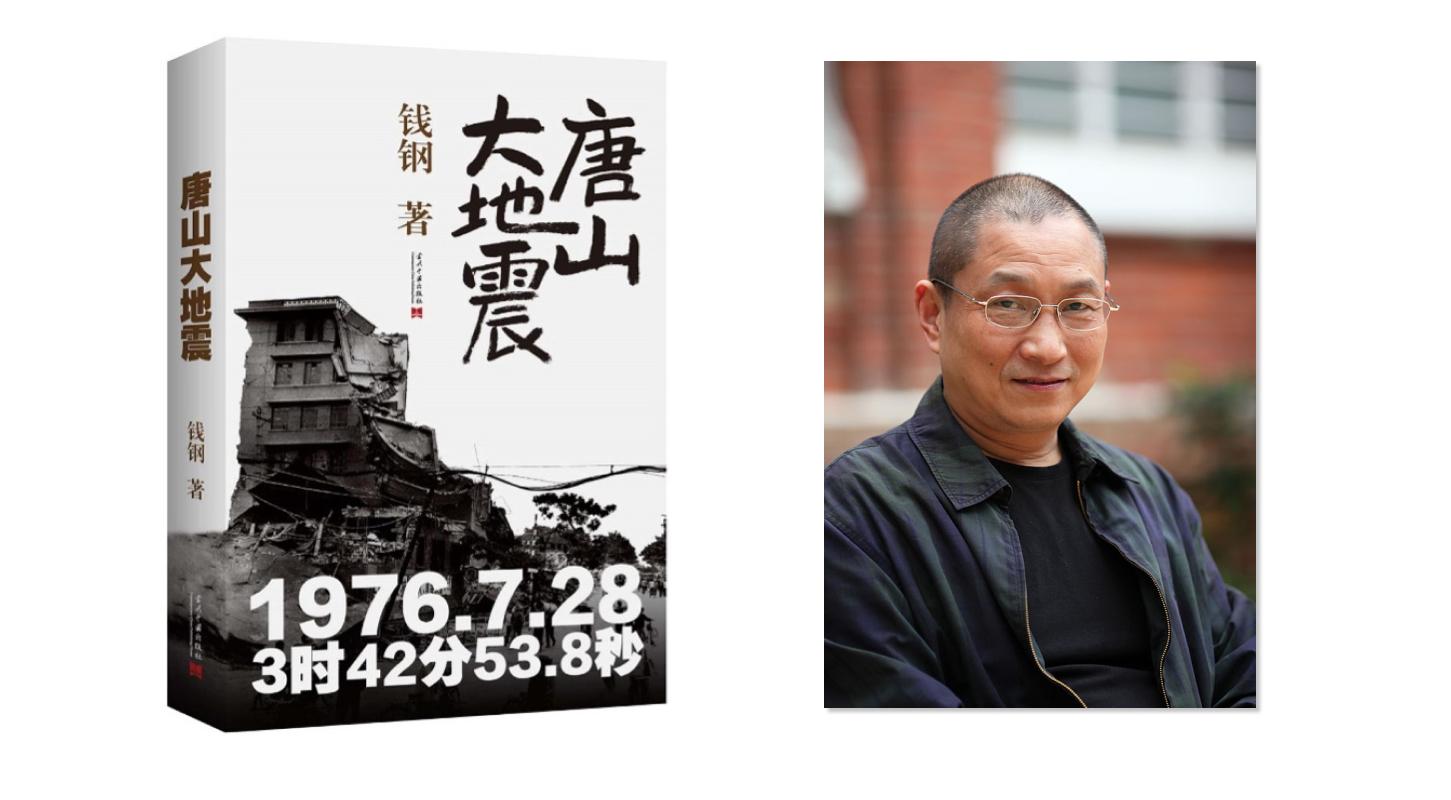

As mentioned above, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck Tangshan in Hebei province on 28 July 1976. The recorded death toll was the highest for any earthquake ever (over 240,000 in the official reckoning), but Chinese media did not directly report on the disaster, and no victims were mentioned. The next day, the People's Daily merely stated that “the great leader Chairman Man and the Party Central Committee were extremely concerned, and sent their condolences, whereas the people of the quake zone, under the guidance of Chairman Mao’s revolutionary ideology, had successfully upheld the revolutionary motto “Man can Conquer Nature” in their disaster-relief efforts. Other commentaries in the paper emphasized “self-reliant disaster relief” to reflect the “great superiority of the socialist system of proletarian dictatorship.” China rejected international assistance from the UN and the international community. The death toll of the Tangshan earthquake was made public only three years later, and journalist Qian Gang was only able to publish his famous book Tangshan Earthquake ten years down the road, a book he states is about “people’s deaths, the human tragedy, what people experienced during the earthquake.”

1978 – 2003: A Multi-stakeholder Model

Following the 'Reform and Opening-Up' period initiated in 1978, the Ministry of Civil Affairs was established to oversee social administration, including a dedicated Rural Social Relief Department to coordinate disaster relief efforts in rural China. Central specialized agencies such as the National Disaster Reduction Committee and the State Council Earthquake Relief Headquarters were also set up.

Since 1980, China has officially accepted assistance from what is now the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). In May 1987, Government-organized non-governmental organizations (GONGOs) such as the Chinese Red Cross and the China Youth Development Foundation began to play a role in emergency response and assistance. When a major forest fire broke out in the Greater Khingan region of Heilongjiang province, multiple Chinese ministries and commissions coordinated foreign aid by setting up a working group. The first time China proactively requested international assistance.

The arrival of international NGOs in China also led to a revival of Chinese non-governmental organizations’ role. The 1982 Constitution of the People’s Republic of China explicitly provided for citizens’ freedom of association. In September 1988, the first administrative regulations specifically about registration and management of Chinese non-governmental organizations, the Administrative Measures for Foundations were issued. The United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women was held on 1 September 1995 in Beijing; the concept of the NGO entered Chinese public discourse, and certain parts of civil society started to become active.

In 1996, the Ministry of Civil Affairs issued a Notice on Giving Full Play to the Role of Charitable Organizations in Social Relief Work, stating that charitable organizations were “a bridge between the government and the people. They have specific strengths when mobilizing social resources and implementing poverty alleviation and relief and play an important role.”

Two more documents were issued in 1998: the Regulations on Registration and Administration of Social Groups and the Interim Regulations on Registration and Administration of Private Non-Enterprise Units. These set a basis for registering non-governmental and non-profit service organizations in social welfare, education, health, and the environment. In June 1999, the Law on the Donations for Public Welfare was passed, the country’s first law on charitable donations.

Political reform led to numerous changes in the news media in the 1980s. Journalist Qian Gang argues that breakthroughs occurred with disaster reporting becoming more human and calling for reflection. But in the 1990s, the trend reversed. No reporting was initially allowed on the 1998 floods, and even later journalists who covered them were subjected to critiques. When SARS broke out in 2003, the official reaction was suppression and concealment of the news, but eventually, the dam burst, and reports began to surface. The official tone later turned towards heavy reporting of the anti-SARS measures.

Book cover of Tangshan Earthquake, and author Qian Gang. Photo provided by Qian Gang.

Nevertheless, the same period saw strong enthusiasm for charitable donations. A 2003 notice from the Ministry of Finance and State Administration of Taxation stated, “In the case of epidemic prevention donations in cash from social entities such as enterprises and individuals, these may be fully deducted for income tax purposes.” This was China’s first tax break in response to a sudden public health incident. Donations eventually reached almost 4 billion yuan.

2003 -2013: The Politics of Compassion

From SARS in 2003 to 2013, the government adopted a “comprehensive coordination” approach to emergency management. The 2003 State Council institutional reform plan tasked the Ministry of Civil Affairs with coordinating and organizing national disaster relief operations, including verification, resource allocation, and coordinating donations. In 2006, an Emergency Management Office was established within the State Council General Office to improve collaboration between local governments and various departments in the State Council. Additionally, an Emergency Response Law was passed in 2007, dividing emergencies into four categories: natural disasters, accidental disasters, public health incidents, and public safety incidents.

The 2008 Sichuan Earthquake marked a breakthrough in disaster reporting. Media outlets, all over the country, immediately dispatched reporters, and tragic scenes from the quake zone were instantly relayed online and on TV. In Qian Gang’s view, what was different this time was the focus on truthfulness and the tragic nature of the disaster, as well as more human reporting – compared to the 1990s’ approach, this formed a "U-shaped" return to the reform spirit in the 1980s. When Premier Wen Jiabao toured the quake zone, the voices of local people crying out were not edited out of media coverage. There were initially numerous media reports of school building collapses (this topic was later censored).

A Korean rescue team working at the Sichuan Earthquake scene on May 17, 2008. Photo taken by Seoul Metropolitan Fire & Disaster Headquarters. Image available at Wikimedia Commons.