Image generated by DALL-E AI system.

Will China’s Electric Vehicle Industry Face Its Own Evergrande Moment?

Amid fierce price wars and aggressive expansion, the turmoil in China’s electric vehicle industry poses a deeper question: how are wealth and risk being distributed across society, and who is left carrying the burden of this transformation?

By Hou Qijiang/Initium

Quick Takes:

- China’s EV industry faces mounting risks of aggressive expansion, heavy debts, and shrinking margins, drawing comparisons to the collapse of Evergrande in real estate.

- Major players like BYD use “quasi-bills” to shift financial strain to suppliers, masking debt and squeezing smaller firms' margin.

- Inefficient “zombie” companies persist as local governments prop them up to sustain economic growth.

- Despite rising exports, Chinese EV makers face significant hurdles abroad, including high tariffs, labor disputes, and incompatible business environments that erode their domestic cost advantages.

- China's NEV boom is driven not only by industrial policy but also by consumer dynamics, but subsidies favorite the middle class and risks borne by buyers, highlighting inequalities.

Evergrande Theory for the Car Industry

"There’s already an 'Evergrande' in the auto industry—it just hasn’t exploded yet," said Great Wall Motor Chairman Wei Jianjun in an interview in May 2025. Great Wall Motor is one of China’s largest homegrown auto manufacturers, and Wei has recently gained attention in China for his blunt critiques, often described as “laying bare the industry’s underwear.”

His reference to Evergrande, once one of China’s largest real estate developers, invokes a cautionary tale. Evergrande's aggressive expansion, heavy debt load, and eventual financial collapse exposed the fragility of China’s high-leverage growth model, sending shockwaves through the property sector. Wei’s comparison struck a nerve, drawing parallels between the overextended real estate market and the current state of China's booming, yet volatile, auto industry, particularly in light of recent price wars and profit pressures.

The turmoil began in earnest when Tesla triggered a price war in China in 2022. Chinese automakers followed suit, driving prices lower in a highly competitive race. Nearly three years on, the industry remains under immense pressure. According to a May 30 report by the respected financial outlet Caixin, China’s Ministry of Commerce recently convened a meeting with industry associations and major automakers, several auto industry experts explicitly warned of severe overcapacity.

Concerns over overcapacity are not new. During a 2024 visit to China, then U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen raised concerns about China’s excess production in key sectors, including new energy vehicles (NEVs). However, NEVs are a cornerstone of China’s industrial policy, forming the leading part of what officials call the “new three” export goods, alongside lithium-ion batteries and solar cells. The NEV sector has become a bright spot in an otherwise sluggish economy. As a result, the Chinese government has offered strong policy and financial support to NEV producers, framing international scrutiny over overcapacity as politically motivated—often citing “U.S. tech suppression” or “European protectionism” in official rhetoric.

Even as Beijing denies the existence of overcapacity, the issue is widely discussed within the industry. In March 2025, Chinese car market research platform Gasgoo revealed that the NEV sector’s average capacity utilization rate was only 51%. The top five automakers—BYD, Tesla, Chery, Xiaomi, and Beijing Benz—accounted for over 90% of that output. Meanwhile, 31 of the 78 active automakers in 2024 produced fewer than 5,000 vehicles per month, raising doubts about their sustainability.

On May 31, both the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) criticized the disorderly nature of recent price wars. In a rare public rebuke, they warned that cutthroat competition was eroding profit margins, threatening product quality, and compromising after-sales service. The CAAM urged leading automakers to avoid selling below cost and squeezing out smaller rivals—a tacit acknowledgment that many companies are “losing money on every car sold.”

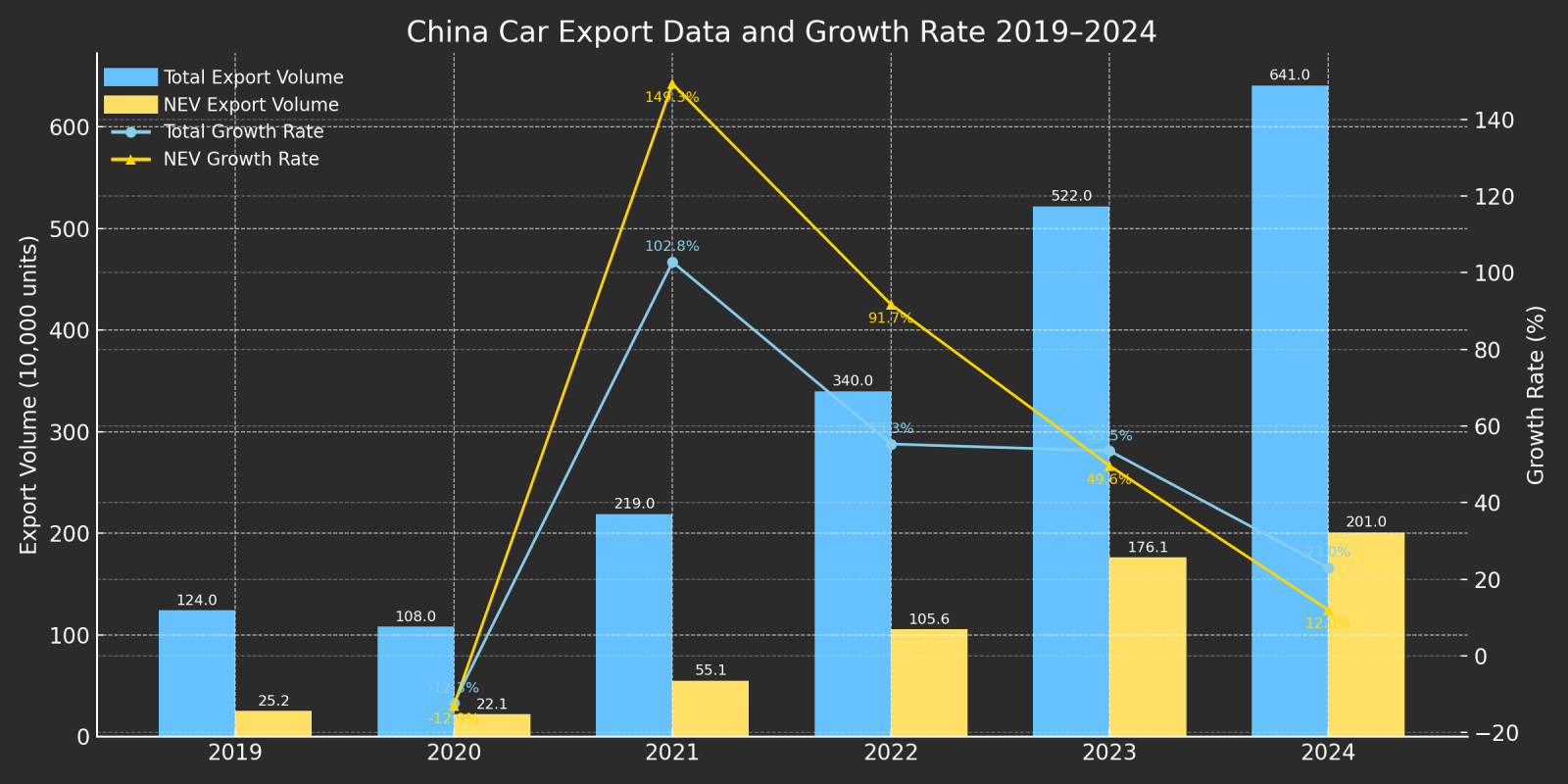

Despite these headwinds, China’s auto export figures continue to surge. Vehicle exports rose from 1 million units in 2020 to 6 million in 2024, according to CAAM data. That same year, NEV production and sales both exceeded 12.8 million units, cementing China’s position as the global leader for the 10th consecutive year. In 2025, NEV penetration surpassed 50%, meaning every other car sold in China was electric or hybrid.

Yet this period of rapid expansion has also brought growing pains. Wei Jianjun’s stark “Evergrande theory” reflects rising anxiety within the sector: while a few dominant players thrive, the rest face shrinking margins, unsold inventory, and an uncertain future.

BYD’s “Quasy-Bills” and the “D-Chain”

Even before the rise of the “Evergrande theory,” several institutions had already raised red flags about the financial health of China’s NEV giants. GMT Research, an accounting firm which had previously issued warnings about Evergrande, published a report in January 2025, criticizing automaker BYD for concealing large hidden debts within its supply chain. Specifically, it pointed to swelling accounts payable and extended supplier credit terms, suggesting that BYD was “addicted to supply chain financing”.

A separate report by Caixin in March 2025 highlighted the use of “quasi-bills” in BYD’s supply chain. BYD issues electronic receivables to suppliers, known as “D-Chain” vouchers. While essentially IOUs (informal documents acknowledging that one party owns a debt to another), these digital instruments also possess bill-like attributes that allow them to circulate or be discounted for early cash redemption at financial institutions, much like commercial paper.

As BYD’s production capacity has ballooned, its use of such financial instruments has expanded in lockstep. Company filings show that accounts payable soared from 22.52 billion yuan (approximately €2.94 billion) at the end of 2019 to 237.52 billion yuan by Q3 2024—an increase of nearly tenfold. By the end of Q1 2025, the figure had climbed further to 250.7 billion yuan. BYD’s debt-to-asset ratio reached 77.91%, remaining at elevated levels.

On May 30, BYD’s head of brand and public relations, Li Yunfei, publicly responded to comparisons with Evergrande on the social media platform Weibo. He dismissed the accusations as a “malicious attempt by certain forces to stir trouble,” citing company data: a 70% debt-to-asset ratio, 580 billion yuan in total liabilities, just 28.6 billion yuan in interest-bearing debt, and a supplier payment cycle of 127 days. Li compared these figures with those of global automakers like Ford, General Motors, and Volkswagen (according to him, Volkswagen alone holds liabilities exceeding 3.4 trillion yuan, including 1 trillion yuan in interest-bearing debt.). He emphasized that BYD is currently operating at its strongest performance in 30 years.

In effect, suppliers have become BYD’s “indirect financiers.”

While quasi-bills are not uncommon in China, especially among state owned and government-backed companies and in sectors like real estate and heavy manufacturing, they are highly controversial. The unequal power dynamics in supply chains enable large firms to convert IOUs into financial instruments, effectively withholding massive amounts of supplier cash. This transforms operating expenses into interest-free short-term liabilities, reducing financing costs while shifting financial strain downstream.

This mechanism has allowed BYD to sustain large-scale capital expenditures without a proportionate increase in formally reported debt. In effect, suppliers have become BYD’s “indirect financiers.” To secure contracts from such a dominant industry player, many small and medium-sized suppliers are forced to pre-finance production, stretching their working capital to the limit. According to Caixin, many are compelled to discount their D-Chain vouchers at rates between 5.2% and 7.2%, further squeezing already-thin margins.

Supporters of BYD argue that high leverage is typical of capital-intensive industries, especially during periods of rapid expansion. They point to BYD’s core strength—its vertically integrated supply chain—as a key reason China can manufacture NEVs more cheaply than most global competitors. They also stress that unlike Evergrande, BYD has not been accused of accounting fraud, aggressive revenue recognition, or audit negligence.

BYD was an official partner of UEFA EURO 2024 in Germany, Source: MSTC.

Still, the comparison with Evergrande is not entirely without precedent. U.S. short-seller Citron Research issued similar warnings about Evergrande as early as 2012, claiming it was inflating assets and downplaying liabilities. At the time, those warnings were largely ignored, and in 2016, Citron’s founder Andrew Left was banned from trading in Hong Kong for five years for allegedly spreading false information. When Evergrande filed for bankruptcy protection in the U.S. in August 2023, Left reiterated on social media that his early warnings had ultimately proven accurate.

While the contexts of the auto and real estate sectors are fundamentally different, the specter of Evergrande’s collapse still looms large in China. In 2021, Evergrande’s use of commercial paper to fund operations collapsed, leading to the suspension of multiple real estate projects—an episode that remains worth heeding.

As a complex manufacturing sector, the auto industry is a sprawling industrial ecosystem. Success depends not just on star manufacturers but also on a complex web of upstream and downstream suppliers and clustered industrial zones. In the era of internal combustion vehicles, most Chinese parts manufacturers were small, technologically underdeveloped, and dependent on foreign companies for critical components. This led to persistent vulnerability to what Chinese analysts call “chokepoint technologies.” According to a 2016 study, domestic suppliers at the time earned profit margins of only 5–8%, while foreign and joint-venture firms enjoyed margins as high as 15–25%. In other words, foreign suppliers earned more than double the net profit for the same level of investment.

Today, while Chinese NEVs have achieved breakthroughs in certain technologies and production scales, the overall industrial strength remains far from robust. China’s auto parts manufacturing sector yields very thin profits. A 2024 white paper by Roland Berger reported that the overall net profit margin of China’s top 100 parts suppliers was just 7.2% in 2023.

Take industry leader BYD as an example: by 2024, it had over 8,000 suppliers. Even among top firms holding key components in the “D-Chain,” profits are extremely slim. For example, Joyson Electronic and Lizhong Group—suppliers of electrical systems and alloy wheels respectively—posted Q1 2025 net profit margins of 2.77% and 2.26%. Huazhuang Technology, a supplier of battery management systems (BMS), posted a 10% margin, with nearly a quarter of its revenue tied to BYD.

In November 2024, a leaked BYD email revealed that the company had asked suppliers to reduce prices by 10% for 2025, calling it a “critical year” for the NEV market. On June 2, 2025, Caixin reported that parts suppliers were urging automakers to ensure timely payments and preserve basic profit margins amid ongoing price wars.

By mid-June, several major automakers like FAW and Geely, along with NEV leaders BYD, XPeng, Li Auto, NIO, and Xiaomi, announced that they would shorten supplier payment terms to no more than 60 days. BAIC and SAIC went a step further, canceling the use of commercial acceptance bills altogether. This marks a significant shift in supply chain finance, aiming to ease cash-flow pressure on suppliers while better managing frequent vehicle model updates and price adjustments. For automakers, it also means that beyond production scale, those with stronger cash positions will gain more control in the supply chain.

“Zero-Kilometer Used Cars” and Zombie Companies

But can the single move of shortening payment terms bring China’s auto price wars to a halt? Likely not. The essence of these price wars is not a malfunction in any one part of the supply chain, but a result of misallocated resources and distorted capacity structures—a reflection of the industry's failure to undergo effective market clearance.

China’s NEV market remains trapped in a price war with no clear winners. According to the China Passenger Car Association, price cuts accelerated sharply in 2024, impacting 227 models, compared to 148 in 2023 and 95 in 2022. The average discount on new passenger vehicles reached 8.3%, with NEVs down 9.2% and fuel powered vehicles at 6.8%. While such cuts might appear to be a natural outcome of market competition, they have not led to meaningful consolidation. Instead, they’ve birthed a growing class of so-called “zombie enterprises.”

In recent years, a number of once-prominent EV startups such as Jiyue and Byton have withdrawn from the market or entered bankruptcy. Many others have become mere shells, surviving in name only. Even when enterprises fall into crisis, many are unable to truly exit, and the market cannot complete a clean sweep.

In addition to his “Evergrande theory,” Great Wall Motor Chairman Wei Jianjun has also criticized the phenomenon of “zero-kilometer used cars” - new vehicles registered and immediately sold as used cars at low prices. The practice is widespread on secondhand goods platforms, with Live-stream sellers in places like Chengdu using it to slash car prices by tens of thousands of yuan.

This gray-market trade reveals the real pressure on the supply side and the out-of-control nature of chaotic competition. On the one hand, continued price cutting places enormous stress across the industry; on the other, even companies that go bankrupt can not fully exit. To understand why “inefficient capacity” cannot be cleared by the market, we turn to a case from a NEV subsector.

Levdeo D50, image available on Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.

Levdeo Auto was once a leader in its subsector, topping domestic low-speed vehicle sales from 2016 to 2018. Known as laotoule (old-man cars), these four-wheeled electric vehicles with speeds below 70 km/h are affordable (under 30,000 yuan), and require no license or registration. Not classified as passenger vehicles, they have long been criticized for poor quality and safety risks, especially due to irregular driving and charging behavior.

During the NEV boom, Levdeo tried to upgrade to high-speed, higher-end EVs. In 2018, with government-guaranteed loans from Changle County in Shandong province, it secured financing via local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) and pushed forward with its transition strategy.

But the costs of transition were steep. As guarantee policies shifted, Levdeo’s funding chain collapsed. In 2023, Levdeo’s founder published a public letter, accusing the Changle County Party Secretary of forcing the company to inflate production data for local political achievement, only to later withdraw guarantees—pushing the company toward failure. A provincial investigation confirmed that production figures were indeed falsified, though it deemed the termination of government guarantees to be in line with national policy.

Caixin interviews corroborated this: a former mid-level Levdeo employee said inflating production and sales numbers was common practice. In 2018—Levdeo’s final year as market leader—it sold about 150,000 units, though it publicly claimed 287,000. The company was largely an assembly operation, lacking any core proprietary technology.

Policy shifts occurred in parallel. As early as November 2018, the Chinese government launched a cleanup on low-speed EVs, banning new production capacity. In 2021, SASAC (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission) issued new guidelines stating that LGFVs in principle should not provide guarantees to private-owned enterprises.

In 2023, the court rejected Levdeo’s bankruptcy restructuring application. However, in 2024, Levdeo entered restructuring proceedings, publicly seeking investors. Since May 2025, Levdeo’s factory has restarted, with some models beginning to sell.

“After the real estate bubble burst, the auto industry became the most important lever to stimulate growth. NEV companies became key targets for investment promotion. If major players like NIO or Li Auto can’t be lured, weaker firms like Haima NEV are welcomed instead. As long as production lines are moving, they can still contribute to local GDP.”

No public records yet confirm the presence of new investors behind Levdeo’s revival. But it is not alone. ZHIDO Auto has undergone capital restructuring, and Southeast Auto has been acquired by Chery. These near-defunct firms are often resurrected through government-business ties, land-for-resources deals, or simply because local governments are reluctant to abandon sunk costs, leave industrial parks idle, or concede failure on past projects.

One automotive media outlet remarked:

“After the real estate bubble burst, the auto industry became the most important lever to stimulate growth. NEV companies became key targets for investment promotion. If major players like NIO or Li Auto can’t be lured, weaker firms like Haima NEV are welcomed instead. As long as production lines are moving, they can still contribute to local GDP.”

This simplistic logic of local investment promotion is not isolated, it is widespread across China. Under the triple pressures of capacity, tax revenue, and political performance, local governments fear missing the next policy windfall. As a result, marginal firms are frequently propped up for another go. In Guizhou, Jiangxi, and Hebei, several NEV projects have “died at launch”, including Qiantu Auto, Youxia Motors, and Greenwheel EV. These zombie projects lack real production capacity, see zero sales for long periods, yet local authorities still hesitate to liquidate them, waiting for potential “buyers.”

After the end of China’s real estate boom, local governments have positioned NEVs as a new pillar industry, offering excessive policy, financial, and resource support. This form of “policy-driven lifeline” has major side effects. Low-end capacity persists, and price wars conceal the presence of non-market competition driven by government backing. National and local support policies have created not only a flurry of projects that appear vibrant, but also undermined the market’s self-cleansing mechanisms. On the surface, China’s auto market suffers from a pricing spiral; Beneath, it is caught in a resource spiral. Price wars don’t eliminate the weak, because this is not a truly competitive market. It is the outcome of multiple layers of intervention.

Going Abroad but Not Yet Landing

The domestic price war has not only reshaped the dynamics of the world’s largest auto market, but also propelled Chinese automakers onto the global stage. Yet stepping out does not necessarily mean stepping up.

Unlike many emerging markets, China’s auto market has neared saturation. Over the past decade, domestic vehicle sales have plateaued within a cyclical range of 25 to 30 million units annually. With the pie no longer growing, competition has become a zero-sum game.

The rapid ascent of China’s domestic auto industry has swiftly eroded the high profit margins once enjoyed by foreign joint-venture brands. In the economy segment, Suzuki, Jeep, and Mitsubishi have exited China, while giants like Volkswagen and Ford have seen market share plummet. General Motors’ sales in China have declined by over 50% from their 2017 peak, raising speculation of a full exit. Foreign automakers have been compelled to abandon the long-standing convention of keeping joint ventures out of export markets, turning instead to deeper integration with Chinese supply chains as a way to absorb mounting overcapacity.

Editor’s Note:

The export strategies of Sino-foreign joint ventures reveal a complex and shifting landscape. China began introducing foreign automotive technologies in the late 1970s, aiming primarily to earn foreign exchange through exports. In 1984, Shanghai Volkswagen became China's first passenger car joint venture. For the Chinese side, a key motivation was that “Volkswagen agreed to allow part of the production to be exported back to Germany, generating foreign currency for China.”

After China joined the World Trade Organization, its domestic car market expanded rapidly, drawing major investments from foreign automakers. According to Chinese media, these companies often included clauses in their joint venture agreements that restricted exports. As late as 2012, analysts still viewed joint venture exports as unlikely to become mainstream, citing unresolved tensions over profit-sharing. Foreign firms prioritized access to China’s domestic market and were reluctant to share export profits with Chinese partners—especially when exports might compete with their home operations. Labor unions in those home countries also objected to offshoring production to low-cost China for re-export.

In 2018, Tesla broke this mold by launching China’s first wholly foreign-owned car factory. By 2020, its Shanghai Gigafactory was operational and exporting to Europe. Meanwhile, traditional multinational automakers—facing shrinking market share in China’s increasingly competitive auto sector— have also begun exporting China-made vehicles to other markets.

The result is a multi-layered competition—not just between NEVs and traditional cars, or between domestic and joint-venture brands, but also a scramble for growth overseas. According to the China Automobile Dealers Association, China exported 6.41 million vehicles in 2024, up 23% year-on-year. Of these, 2.01 million were NEVs—a 12% increase. In the first quarter of 2025, China exported 649,000 NEVs while importing only 13,000, resulting in an overwhelming trade surplus.

But for Chinese automakers, venturing abroad does not guarantee increased sales or strategic success. Entering new markets often dissolves prior competitive advantages. China’s nascent vehicle export boom has already run into the wall of global trade protectionism. In June 2024, the European Union imposed provisional anti-subsidy tariffs on Chinese-made EVs up to 45.3%.

Simultaneously, the United States and Canada raised tariffs on Chinese EVs to 100%, Brazil to 35%, and Turkey to 40%. Russia, once seen as a beneficiary of geopolitical dislocation, has also tightened controls. Since April 2024, it began requiring tax differential payments for imported vehicles via Central Asia. According to industry data, China’s auto exports to Russia dropped 44% year-on-year in Q1 2025, totaling only 99,000 units. The “war dividend” once offered by the Russian market has faded.

Faced with rising barriers, many Chinese automakers are shifting to overseas production to bypass tariffs. Yet factory-building abroad is no copy-paste of China’s low-cost model. Instead, it has exposed deep structural incompatibilities in business environments. Consider BYD’s plant in Brazil—intended as its first full vehicle assembly base outside Asia and a cornerstone in its globalization strategy. By late 2024, the factory became embroiled in major labor disputes. In November, Brazilian media reported serious labor rights violations at the site, including a shocking accident in which a worker lost a finger due to safety lapses.

Brazilian labor prosecutors filed lawsuits against BYD and two contractors, alleging slave-like working conditions and international human trafficking. In December 2024, 220 Chinese workers were found in “conditions akin to slavery,” according to prosecutors.

These problems reflect long-standing patterns in China’s domestic auto industry—labor-intensive, high-pressure, and low-wage jobs, often obscured by the country’s unique market conditions. Public labor arbitration records show that one gluing technician at BYD worked 441.5 hours in a single month for just 9,271 yuan (€1,177).

Even bypassing tariffs through foreign capital partnerships doesn’t always bear fruit. HiPhi, a Chinese EV startup positioned in the high-end intelligent vehicle segment, stumbled into crisis amid intensifying price wars. After a failed attempt to attract Middle Eastern investment in 2024, it reached out to EV Electra, a Lebanese EV startup founded in 2017, in May 2025. EV Electra’s founder, Jihad Mohammad, has a murky background: a history of crypto ventures, unproven EV plans across multiple regions, and allegations of fraud and plagiarism by Swedish media. While HiPhi announced foreign investment from EV Electra, no funds have materialized, and the investor’s credibility and actual capacity remain highly suspect. HiPhi has not resumed production.

In sheer speed and scale, China’s NEV industry has achieved impressive success. In 2024, the average price of a new car in China was only $19,000.00 (€17,480.00)—half that of comparable models in the U.S. or Europe. The development cycle for a new Chinese car model is also roughly half that of traditional Western automakers. The advantages European automakers spent half a century building in the fuel-powered car era have been eclipsed in just a few years by China’s rise in EV technology. Many Chinese analysts attribute this leap to China’s demographic and manufacturing dividends, acknowledging that the industry’s current turbulence is an inevitable price for such accelerated overtaking.

Yet, without breakthroughs in technological innovation, brand equity, or institutional reform, the model that enabled China’s rapid ascent may not translate abroad. Advantages rooted in local asymmetries will diminish as companies step across borders into unfamiliar regulatory and economic systems. What looks like momentum today may reveal a fragile foundation tomorrow—an industrial miracle increasingly vulnerable to the weight of its own systemic dependencies.

Politics of Demand:

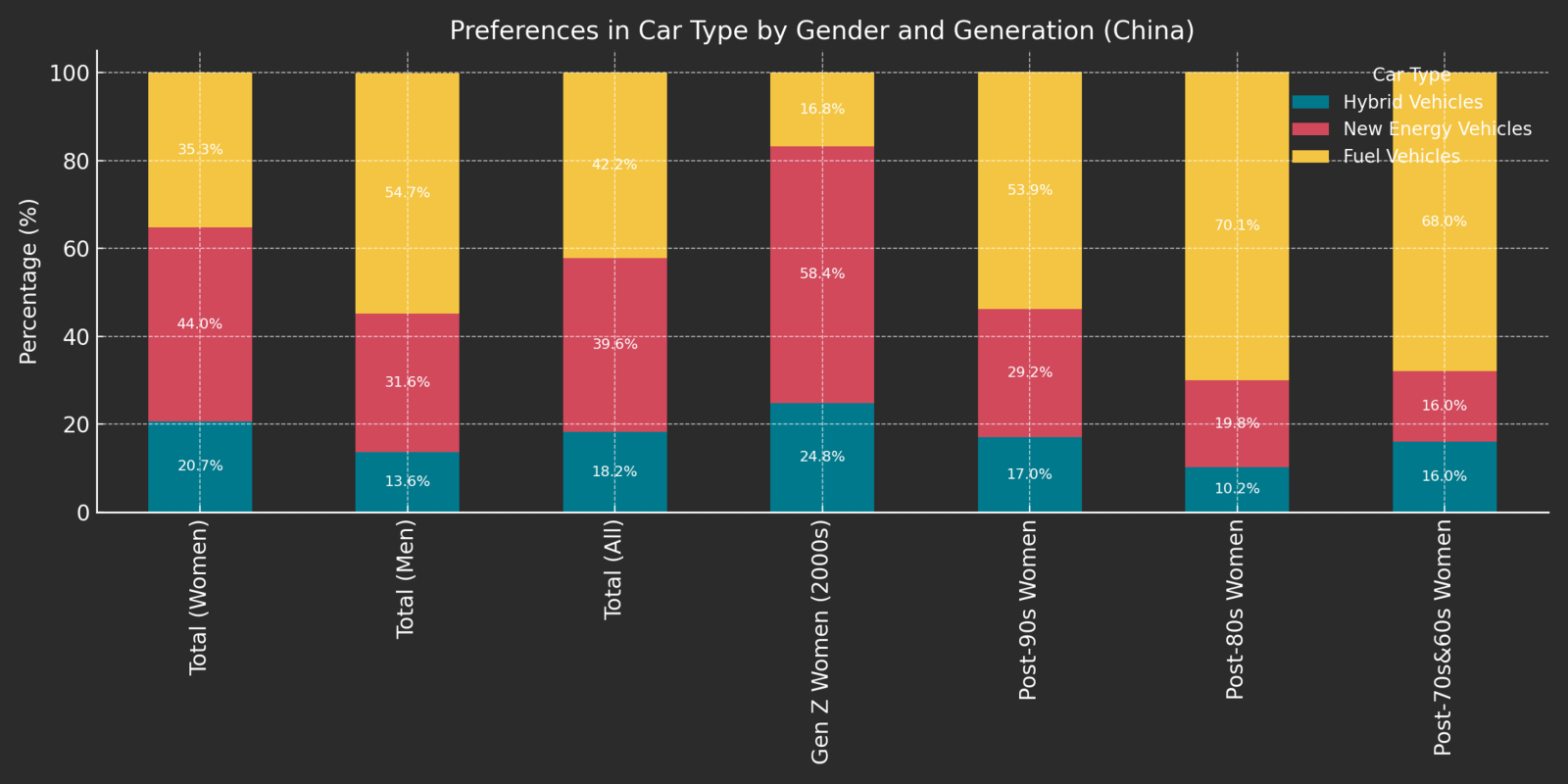

International observers tend to focus on the supply-side of China’s NEV boom—government subsidies, industrial policy, and corporate strategy. But the demand-side, particularly consumer behavior and social dynamics, is equally crucial—and often overlooked.

On the evening of March 29, 2025, a Xiaomi SU7 veered into a highway barrier in Anhui Province and caught fire, killing all three passengers—female university students in their early twenties. The tragedy sparked intense debate over the boundaries of responsibility in intelligent driving systems and triggered a fierce public relations battle online. It also came at a time of massive NEV expansion, cutthroat domestic competition, and escalating trade tensions—making the crash one of the few occasions where ethical and legal concerns—usually overshadowed by techno-optimism—briefly surfaced in public discourse.

The victims fit squarely within Xiaomi’s target demographic. In the aftermath, one of them was singled out for having received the SU7 as a gift from her boyfriend, prompting a flood of misogynistic comments on social media — accusing her of being ‘too weak to brake’ or claiming it was ‘inappropriate for an unmarried woman to accept such an expensive gift.’” Beyond these gendered attacks lies a deeper truth: As China’s car market approaches saturation, women—who historically own fewer cars—have become a key growth demographic. Automakers, including Xiaomi, have gone to great lengths to appeal to this group. CEO Lei Jun even spotlighted female consumers during a major company event.