Jin Yan visited Berlin, Germany. Photo provided by the Interviewee.

Russia: enemy, friend, or lesson for China?

Prominent Russia and Eastern Europe expert Jin Yan gives some historical perspective on Sino-Russian relations and why it is futile to expect China to pressure Russia to end the war.

Quick Takes:

- Sino-Russia relations have experienced ups and downs throughout history. In 1969, when the Soviet Union threatened nuclear war against China, China sought to improve its relationship with the U.S.

- Nowadays, China's reliance on Russia is due to a narrowing path in its foreign relations, anti-America policies, and a misperception of Putin as an ideological ally.

- While Sinophobia sentiment is unrestricted in Russia, critical voices from experts warning about China-Russia relations are often silenced in China.

- It would be wishful thinking for Europeans to expect China to exert pressure on Russia to end the ongoing war.

Jin Yan is well known in China as a Russia and Eastern Europe expert and a former Director of the Russian Studies Centre at the Central Compilation and Translation Bureau, CPC Central Committee, as well as an ex-Professor at China University of Political Science and Law.

Echowall:Professor Jin, welcome to our Echowall Podcast today. You are one of the most authoritative Chinese experts on Russia and Eastern Europe. Why did you choose this specialism, and can you share some of the highlights of your career?

Jin Yan: I have to demur on that; I’m not the best-known expert in this field; I’ve just been doing it a long time. When it comes to my career and how it started, maybe it’s not easy for you to understand, but we didn’t have much choice growing up in the 1950s. People lived and worked as a production team, which for educated urban youth meant being sent to the countryside.

Learning Russian Because of a War

Sino-Soviet relations have been extremely tense since the late 1950s, and no one learned Russian anymore. After the Battle of Zhenbao (Damanski) Island in 1969, there was a need for Russian speakers. From 1971 onwards, China started recruiting so-called worker-peasant-soldier students to study Russian. The intakes before me were all from the military or intelligence services. Perhaps the government also needed non-military people to learn Russian, but that was the backdrop to my studying it. After the course, I returned to the school where I had worked.

A Soviet T-62 tank intercepted by the Chinese People's Liberation Army during the Zhenbao Island conflict. Image from the book Down with the New Tsars! available at Wikimedia Commons.

English had become increasingly fashionable then, so that’s what the school wanted me to teach. Now if you think about it, there’s a huge gulf between the Russian and English languages, but thankfully English is quite simple, so I could learn it at the same time as teaching it.

The first intake of graduate students to Chinese universities after the Cultural Revolution was in 1978 after Deng Xiaoping reinstated the college entrance exam the year before. You could say that this opened a door for people. I wanted to apply to study Russian Literature, but it wasn’t on the menu in 1978. My alma mater at the time offered Russian and Eastern European History majors. There wasn’t any choice, and for me, it was exciting enough to attend university.

The Zhenbao (Damanski) Island incident

In 1969, armed conflict occurred between China and the Soviet Union over the ownership of Zhenbao (Damanski) Island in the Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin, worsening relations between China and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union considered a pre-emptive strike against China, and Mao Zedong turned to the U.S. for help. President Richard Nixon made a historic visit to China in 1972.

After graduating, I researched and taught Soviet and Russian history and worked on the transitions Russia and Eastern Europe had been through. Born in the 1950s, I’d experienced the Sino-Soviet honeymoon of back then and the later split and the clashes between them. We even saw the Soviet Union’s attempt at nuclear deterrence.

A big part of why I learned Russian was because we had to teach the army how to talk on the battlefield. We were made to teach the soldiers some basic phrases such as “drop your weapons,” which shows that China’s higher-ups were expecting a war involving face-to-face combat, and the whole of Northwest China would be the front line. China captured a T-62 tank from the Soviet Union after the Zhenbao (Damanski) Island incident, which was subsequently displayed at the Military Museum, and 1:10 scale models were sent out to every army unit; this was going to be a tank war.

Later on, China pulled way ahead of the Soviet Union in reform terms. So, we have a saying on Sino-Russian relations: “Russia as a friend, Russia as an enemy, and Russia as a lesson.” Reform in Russia wasn’t followed up properly, so of course, in relative terms, they’ve got a lot to learn from us. Right now, Russia’s economy is the size of Guangdong province’s. My personal experiences are a microcosm of the ebb and flow of Sino-Russian relations.

Experiencing Eastern Europe’s Transition

Echowall: You also studied in Poland between 1990 and 1992 and had personal experience of the giant rifts in Eastern Europe; can you tell us about your life at the time?

Jin Yan: Everyone was in a state of confusion after 1989. No one knew what direction China was heading in. I wanted to get to know Russia and Eastern Europe, which were transitioning, but most Chinese people couldn’t see what was happening. My colleagues thought of me as their eyes and ears, like their telescope extending to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. They told me they didn’t believe the official reports and wanted to see things in those places through my eyes.

At first, I had to go and learn Polish in Poland, but seeing as I had a Chinese ‘service’ (rather than a private) passport, I could enter the USSR any time without a visa. I had a lot on my plate with learning Polish at university there; when those dramatic changes swept Eastern Europe, a process of de-Sovietization took place in many countries, which primarily showed up in the language. Foreign students who in the past would have taken Russian were now encouraged to learn the local language instead.

I had a real headache at the time. I had a lot of language learning to do. And I had a strong desire to understand Soviet as well as Eastern European society. Ultimately, I realized I had to get out of the classroom to see more.

I went to the Soviet Union a few times, to what was later called Russia. I was at the Kremlin, watching many journalists with their tripods doing their interviews, watching the flags being changed.

Of course, I also wanted to learn more about Polish society besides just the language. I needed another prism; I needed to learn it by doing something; I couldn’t just hand out questionnaires on the street. Then fate intervened - a professor from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences was teaching taiji at a cultural center, and he asked if I wanted to give it a go. Maybe I could teach taiji and Chinese cuisine. I wasn’t good at either, I would cook ten Chinese dishes, and they’d all taste the same, and I’d never actually studied taiji. But I knew it wouldn’t be too hard.

So later, I taught taiji to a bunch of kids. When we were on breaks, I would ask how their families and how their parents were doing. How did they see the upheavals of the day - these questions were easy to ask. The dialogue was straightforward because they really wanted to understand China, and I wanted to understand Poland. I taught Chinese cooking to a bunch of aunties, and the aunties were enthusiastic too. At the time, it was like doing a cooking show on TV, except it was all the stuff people brought. Some brought along gas stoves, and others came with plates.

I sent many letters back to China after these experiences. I wrote maybe three or four hundred letters. I would write one letter a day, sometimes two. Sometimes I would go to the Chinese embassy and ask their couriers to take the letter back to China. Sometimes I would go to the airport, put Chinese stamps on the letters, and ask a Chinese person to take them back to China for me (to post).

I didn’t have prejudices. I know some of the people I taught had their limitations, but so did everyone else around you. You just come to your conclusions. At the time, many Chinese people wanted to understand Eastern Europe. I later wrote several books, Travels in New Russia, Ten Years of Vicissitudes, and From Eastern Europe to a New Europe, sharing everything I saw and experienced. I went to the Soviet Union six times during that period.

I traveled a lot, went to mines and farms, and intentionally sought out people from different class backgrounds. Later this all became material for my books.

Warning about Russia

Echowall: Regarding post-Soviet Russia, you were an early critic of Putin’s nationalism and imperial visions; you warned people in China not to have any illusions about it. When did you begin to have doubts, and how did you warn people in China?

Jin Yan: As historians, we start with the historical record and then move to the present day. Then we go back from present-day reality into history. We take a very long-term perspective. Others do short-term, up-to-the-minute work, whether in intelligence or news reporting; they only focus on one thing. Perhaps they also suggest solutions to problems but lack a historical overview; they miss the things you only see from a long-term, horizontal sweep when comparing different countries worldwide. You’ll fall into a narrow point of view when there’s only one thing you’re focusing on.

If you take a long view of history, you realize that what’s happening now has occurred in other countries, perhaps multiple times in Russian history too. So, what is the root cause? If you just want to know what’s going on, it’s incredibly easy because we now have swathes of language specialists. But the important thing to grasp is why these things happened in the first place. People like me we’ve long been studying Russian history and Soviet history too; we know about various historical characteristics Russia has. We ought to be allowed to share what we know.

A diversity of voices was allowed during the [previous] Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao era. But now things are more restricted. Sometimes I go to some symposium or other, and I ask them up front if there’s going to be censorship, and they say yes. So, then I ask what people like me are supposed to be doing there. They then tell me it’s because the leadership has had some ideas, and they want these ideas to come out from the mouths of the scholars. I reply that they can count me out of this sing-along session.

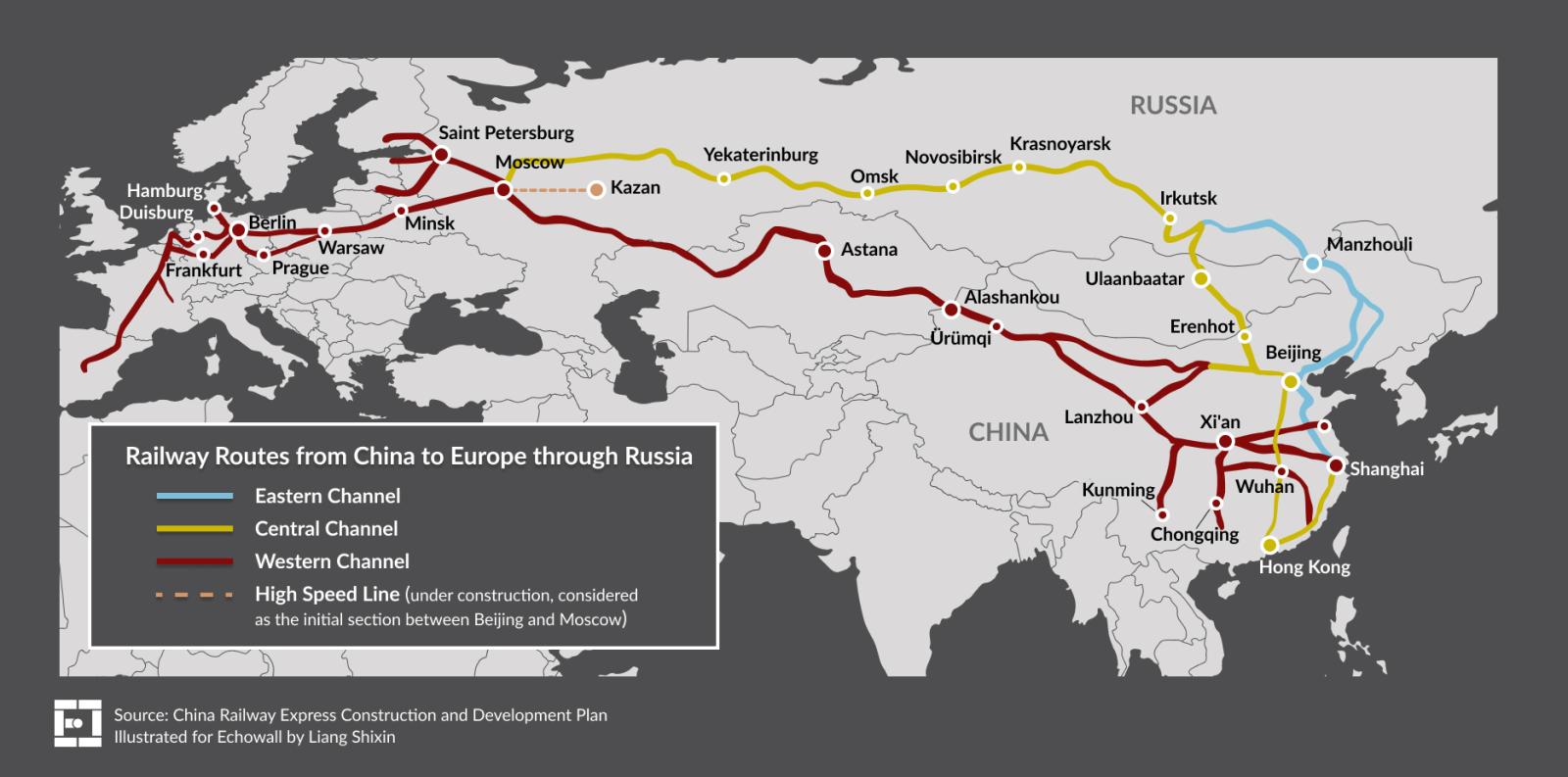

China started to buy crude oil from Russia in 2000. In 2009, the two countries signed an Inter-governmental Agreement on Cooperation in the Oil Sector , including a Loans-for-Oil contract, a pipeline construction agreement, and a long-term crude oil supply contract. Since then, through further infrastructure constructions and long-term contracts, China’s imports of Russian crude oil have quadrupled. In 2016, Russia surpassed Saudi Arabia as China’s biggest oil supplier.

I did raise various issues before, like with some of the railways built under the Belt and Road Initiative or subsidized projects. I argued we ought to look hard at the rationales. It’s taxpayers’ money at the end of the day; you can’t just let it go to waste.

They had all kinds of people coming to these symposiums, some in intelligence, others in the military, yet more from Xinhua News Agency, and they were all taking different positions. Lots of the armed forces people said they don’t care about the economics, just the politics, because we apparently need to be anti-US right now. I talked about oil imports from Russia: you must consider oil prices. You have to realize that you’re getting into long-term contracts, which means you have to think about the future, so you need projections or at least feasibility studies.

And how many loss-making [high-speed] railways have we already built? Now you’re talking about building another one. What capacity is it going to have? I think, as a scholar, I must ask these questions. I was hoping that someone would offer a rebuttal, that they’d convince me. You can’t just say something’s been decided based on a political calculus, and then we sign a big check, then that’s the last that gets heard about it.

Nowadays, though, I’m discovering these critiques are increasingly unwelcome. But I go on telling people that there are a couple of Russian characteristics, and you mustn’t forget them. The first characteristic is that I don’t think Russia has any principles, and they have always been changeable and unpredictable.

In March 1918, Lenin signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, despite widespread opposition. He signed over a large part of Russia and Ukraine to Germany and agreed to pay 6 billion marks in compensation. He reneged on the agreement in November, saying the terms were void. That was less than a year later.

Lenin said the agreement was just a scrap of paper. At the time, Lev Karakhan, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, said that once the Soviet Union was established, all territories taken from China by Tsarist Russia would be returned without conditions. The Chinese people were overjoyed, and surveys said 59% saw Russia as a friend of China. So, did the Soviets give all the land back? None of it, and they only said they would do it for political purposes.

Putin’s Allies

That’s the kind of place the Soviet Union was, no principles. Meanwhile, in China, there is too much wishful thinking and conjecture towards this neighbor of ours, especially from the current leadership, and the gist is “we think he will be our ally.”

Putin has said that Russia only has two allies: the army and the Navy. Although their army and navy have shown up this time, the technology and material are only slightly better than during the Second World War. When Putin came to power, we saw him as a mishmash of red [communist] and white [Tsarist] ideology, and later there was less and less red, leaving just the white behind. The Chinese leadership has been ideologically seeing Russia as a kindred spirit, but they’ve stripped out the red communist part from the Soviet version. What’s happening is effectively a return to Tsarist Russia.

Of course, there is a process to how Putin changed his mind. The collapse of the Soviet Union came as a great relief to the West, and this big polar bear was now looking like more of a poodle. I think the West, however, was quite short-sighted about this. They thought Russia was now second-class, that there was no need to take it seriously anymore.

I remember talking to some diplomatic advisors while in the US. I told them that no matter what happened, research on Russia had to be prioritized and thorough. They couldn’t allow it to go slack. West Germany got the Marshall Plan that enabled it to emerge from the shadows of World War II. Conversely, Russia suffered a long-term hit to national self-esteem after its dramatic transition from the USSR and realized they were now a second-class country.

Russia made a lot of noise about getting Schengen visas. Tiny Caribbean countries were able to get them seamlessly, but they wouldn’t do it for Russia, which led to a backlash in Russia: if they couldn’t be friends, they’d rather be enemies. They felt they’d only be taken seriously as enemies and ignored if they were ‘friends.’ Another example: there used to be a lot of grant funding given to Slavic research institutes in the US and Japan, but it dried up immediately after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and it felt like they weren’t being taken seriously anymore. They could be ignored. That kind of thing paved the way for what’s happening with Russia now. Of course, the main cause is still internal, with factors to do with Russia itself. Still, there’s also been an element of this feeling of ostracization and exclusion by the outside, leading to a general groundswell of nationalism in Russia.

And so, I’m constantly emphasizing two points: First, you need to be wary of the Russians. Second, we have to do serious work on Russia. Only by doing this will we be able to come up with some rational proposals: how to do prevention and what scenarios to work with. But many people [in China] go for the simpler approach: the political need to have the Russians as our allies.

When the Russians wanted to do nuclear blackmail against China in 1969, the US filled China in on the facts. There were negotiations between China and the US, and to prevent the KGB from eavesdropping, they did them as silent discussions in a secret room on the water at Warsaw’s Łazienki Park. Both sides wrote messages in English and passed them over. The whole discussion was done in silence. That just goes to show how worried they were about the KGB. And nowadays, you’ve got some Chinese people who are completely convinced Russia should be one of our allies! It may be that this is a product of our current diplomatic situation, as we’re getting more and more isolated.

Echowall: You have experienced the ups and downs of Sino-Russian relations and the uneven relationship between China and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union was China’s ‘big brother.’ For many Western commentators, though, that relationship has been reversed: China, with its immense economic resources, is now the ‘big brother,’ and Russia is slowly becoming a subordinate of China. Would you say this is correct?

Jin Yan:I don’t think it is correct because there’s economic size, and then there’s political influence. We can’t measure China’s need for Russia just in economic terms. I think the current ‘wolf warrior’ trend in diplomacy has given this impression – a kind of Chinese self-confidence that can influence the world. But really, China is like a frog in a well, isolating itself from the world.

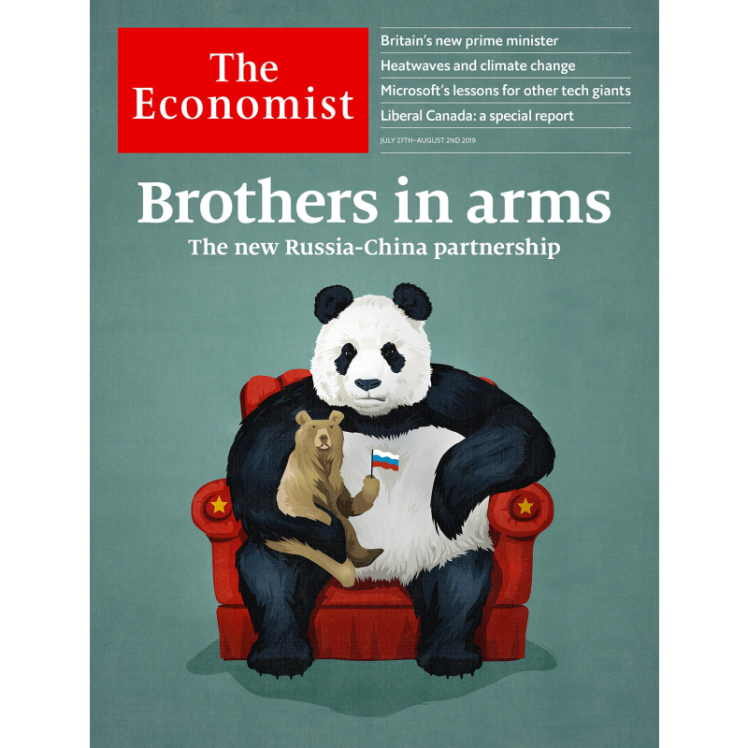

Cover of The Economist, a panda cradling a small bear. Issue 2, July-August 2019

I feel the understanding of Russia in China right now is sometimes lower than some enlightened people back in the late Qing Dynasty. Lin Zexu [a Qing dynasty official better known for cracking down on opium] said, “Russia will be the ultimate pitfall for China.” In contrast, Zeng Guofan [a famous statesman and military general] had said that while Britain was devious and France only slightly less, the US could be useful for China. Even in the Qing dynasty, these people had a grip on world trends and how they would play out diplomatically. Right now, I would say China has tied its own hands diplomatically, or, if you like, the country’s only in conversation with itself, without any interaction with the outside.

China’s path is now becoming narrower. We have fewer and fewer friends, so there’s more and more forced reliance on Russia. We can’t just view this predicament economically. Things aren’t like that Economist cover – a panda cradling a small polar bear - that’s incorrect.

I think the other reason is China’s current approach to diplomacy, which draws a direct parallel between state diplomacy and ‘emperor’s diplomacy.’ Maybe the latter has replaced the former. We shouldn’t look at the needs of the rulers and the national interest as the same thing. Overall, I think the way the West perceives Sino-Russian relations is at some variance with reality.

We shouldn’t look at the needs of the rulers and the national interest as the same thing. Overall, I think the way the West perceives Sino-Russian relations is at some variance with reality.

Sinophobia in Russia

Echowall: You have also talked about the long history of anti-China sentiment in Russia, but there are very few people currently sounding the alarm about it in China. Why?

Jin Yan: They don’t get heard. Officialdom doesn’t want these diverse opinions to be heard. What you end up hearing instead is the same refrain everywhere. It would be more normal to have a variety of views. Now in Russia, you can criticize China and the anti-China voices get heard. We’ve been trying to draw attention to the widespread Sinophobia in Russia. Russia will say they have a free press and don’t control the media, but this is just sophistry. They’re pinning some of the blame on the media - so why can’t we do the same thing in China? China is terrified across the board that discordant views will negatively affect Russian relations. But there ought to be different voices to decide policy more freely.

Echowall: So, when did there start to be Sinophobia in Russia?

Jin Yan: There has always been that current, especially in the past few years. Did you know that there are 1.5 million square kilometers of territory that used to be part of Northeast and Northwest China but were taken by Russia [in the late 19th century]? Maybe today, Russians have realized that China’s a lot stronger now and might want to settle some scores. You did have Lenin saying he’d return that land back then. Are we going to try and cash in this pledge now? Of course, they’re nervous.

Therefore, Sinophobia has always existed in the Russian Far East. And Moscow has used anti-Chinese politicians such as Yevgeny Nazdratenko in the Far East [Nazdratenko espouses a ‘yellow peril’ theory]. The Russian Far East is so underpopulated they have whole cities built on the tundra, which are now abandoned. So, the Russians are worried about the Chinese coming in, which would mean this whole swathe of the Far East turning Chinese immediately. And so they make sure to pick local leaders who are anti-China. Let’s just take the rules for buying a home; for example, the Russians are allowed to come over the river to buy houses in the Chinese city of Mohe, but the Chinese can’t do the same in Russia.

From the perspective of ordinary people in Russia, China looks like a nouveau-riche country. They know that you’ve done well economically, but they feel a great sense of disequilibrium at the same time.

When Putin spoke at Peking University in the Jiang Zemin era, a Chinese student asked him: you have heard President Jiang speaking Russian; why aren’t you speaking Chinese?

Now, of course, that’s a bold question. Putin did quite well on the spot, though. He said that his daughter was a big fan of Chinese culture; she’s learning Chinese cooking, kung-fu, the Chinese language, and so on, and he managed to dodge the question. The episode did annoy Putin’s staff, though; they thought the Chinese had been offensive. They’ve always taken line with us, ‘It’s always been you that learns Russian; we don’t have to learn Chinese.’ In the Third International [Comintern], the CCP was a branch entity under Soviet tutelage. All this shows that Russia will always look down on China and see it as a student; their ‘Greater Russia’ views are unchanged.

Will China help to end the war?

Echowall: The next questions are to do with the Ukraine war. What is the relationship like between China and Ukraine? Has there been any change before or after the war?

Jin Yan: Ukraine is an original constituent Republic of the Soviet Union with a powerful military. China has imported countless military planes from Russia and Ukraine, as well as the Varyag, which now serves as an aircraft carrier of ours. There’s also the matter of food imports. Ukraine is a huge exporter of food to China, but I think given a choice between Russia or Ukraine, China would officially go for Russia. There have been countless UN resolutions, and China has mostly abstained from them – obviously, we didn’t want to offend Russia.

Even though China and Ukraine have a normal relationship, everybody can see that in this war, Russia blatantly sent troops into a country that had its sovereignty, a clear aggression. These basic questions of right or wrong ought to outweigh any considerations of interests. China also has the Taiwan issue to contend with. If you can just run a referendum for separation [in East Ukraine], what’s to stop Taiwan from doing the same? But despite these issues, China’s official pro-Russian stance is still extremely obvious. Of course, people like me don’t have access to internal information, and we don’t know what kind of supplies have been shipped. But one thing is clear from their attitude: when it comes to basic questions of right and wrong, China takes Russia’s side; that’s what everybody understands.

Echowall: What is China’s current view on the war between Russia and Ukraine? In officialdom, academia, and on the internet, is there a diversity of views and takes?

Jin Yan:Let’s forget what officialdom thinks. On the internet, you get all sorts of people and a wide spectrum of opinions. Many people online support Ukraine; they’re waiting to see if Putin becomes a laughingstock. There are also some military analyses about specific battles and how each was fought. But if these don’t follow the official line, they still won’t be allowed to be published. In reality, officialdom says what it says, unofficial views say what they say, and there’s seldom any interaction or convergence between the two.

Echowall: Some European politicians and analysts think we can call on China to persuade Russia to stop the war, and then everything will be peaceful again. Do you think that’s a possibility?

Left: Washington Post coverage of Macron's meeting with Xi Jinping. Right: BBC's report on Scholz's meeting with Xi Jinping.